This article is the first among a series of articles describing the subject of Secure Computing.

Say we have a function \(F(x_1, x_2, ..., x_n) \rightarrow (y_1, y_2, ..., y_n)\) that takes n inputs and has n outputs. Me and n-1 of my friends (i.e. we are n people in total) have secret numbers. Let’s number the people \(p_1, ..., p_n\) and the secret numbers \(x_1, ..., x_n\) (i.e. person \(p_i\) knows secret number \(x_i\)). We want to perform a process after which person \(p_i\) will know \(y_i\), where \(y_i\) is the i’th output of F computed on the \(x_i\)’s, but they must not know anything else. Let me give you an example:

Say that there are 3 people, each having a monthly salary of \(x_i\) dollars (for i=1, 2, 3). They want person number 1 to know the sum of the salaries, person 2 to know the product of the salaries and person 3 to know the maximum of the salaries. But they do not want to reveal their salaries to each other!

A simple solution would be to find a new and neutral person that all of the men trust. They would then reveal to him all of their salaries, one by one, and this neutral person will perform the calculation and tell them the results. The goal of this series of articles is to solve this problem without using such a trusted party.

Before we begin to think of a solution, let’s notice some inherent problems:

- The men can lie about their salaries. Since it is assumed that only person \(p_i\) knows \(x_i\), they can lie about it (i.e. input another number, say \(x_i'\) instead of \(x_i\)). There is obviously nothing that can be done about it. We will therefore assume that all of the men (while they may try to cheat at other parts of the protocol) will input their true numbers to it.

- The function itself may leak back information about the secret numbers of the other people. For example, if there are only 2 people, and \(y_1\) is the sum of the \(x_i\)’s and \(y_2\) is their product, then after the process each of the men will know the secret number of the other (as the function is reversible). This is simply not considered a problem, as our goal was to do without the trusted party, and if for some reason the function is reversible (or semi-reversible) then the same problem will arise with the trusted party protocol, which is what we are trying to emulate.

The solution will consist of several parts (which will be dealt with in the other parts of this topic):

- Performing a Zero Knowledge Proof (ZKP) of a generic NPC problem.

- The “Oblivious Transfer” protocol.

- Transforming a general function \(f(x_1, ..., x_n)\) to a circuit consisting only of XOR gates and AND gates.

- Solving our problem for the specific cases where our function is a XOR gate or an AND gate.

So now, after we have set our goals, let’s dive in to the the first step:

Zero Knowledge Proof of an NPC Problem

At this point, I rather not formally define the exact meaning of a ZKP. I will instead try to explain is intuitively. Say I know the answer to a complicated puzzle and you don’t. The process of me convincing you that I know the answer, without you learning anything about it, is called a Zero Knowledge Proof.

Let me give you this neat example (inspired by Applied Kid Cryptography). Say we are playing the game of Where’s Waldo? with this picture (click to zoom):

BTW - for the purposes of this post, I built a Where’s Waldo generator - some more on that below. In this specific case, waldo looks like this:

After minutes of contemplation, I suddenly find him! The following dialog then takes place between us:

Me: “Yes! I found him! Wow, he was really well hidden.”

You: “I don’t believe you! Its too hard! You must be lying!”

Me: “No, seriously. He’s right there, next to the…”

You: “Go on - Where is he?!”

Me: “Well, I do not want to ruin this for you… This is such a cool puzzle…”

You: “I knew it! You are lying - you haven’t found him.”

The situation becomes frustrating for me! How can I prove to you that I know where Waldo is without revealing his location?

I can give you a general fact about his location (for example, that he is near the center of the picture and not near the borders) and later when you will find him too, you will be able to verify that I was indeed right.

There are obvious drawbacks with this method:

- While not revealing exactly where Waldo is, a lot of information is still leaked (you now know not to look for him in the sides of the image).

- I can lie to you with a good probability - even if I haven’t found him my general statement may be right.

- And finally, the biggest drawback is that you may still not be convinced (i.e. we have to wait for you to find him as well).

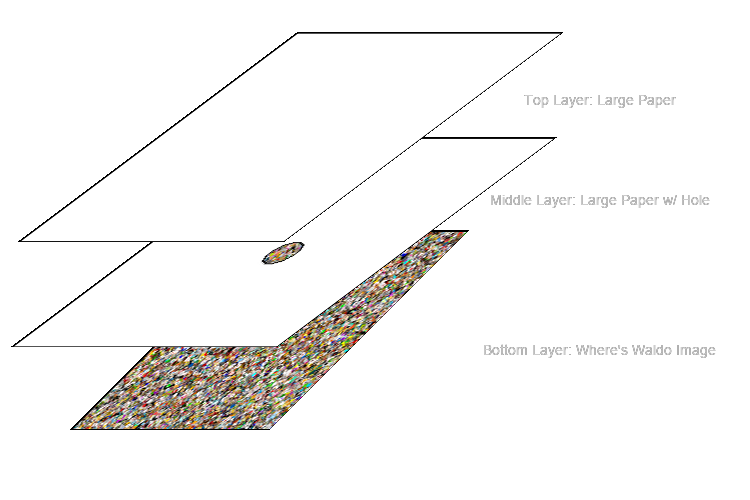

Suddenly it hits me! I know what to do! I take a big white piece of paper (much bigger than the original image, say twice as big in every direction). I then place the original image at a random location beneath it and cutout Waldo’s location from the paper. I then place another big piece of paper on top of everything (this time, without the cutout):

My illustration is not drawn to scale - the covering papers should be much bigger in reality.

You then choose a number: 1 or 2. If you choose 1, I remove both pieces of paper, revealing to you the entire image. If you choose 2, I remove only the top piece of paper, revealing to you that I know where Waldo is, as such (again, not drawn to scale):

What does this accomplish? Well, first of all, if indeed I know where Waldo is I can answer both of your questions. If, on the other hand, I was lying, and I put the original image under the papers, then I could not have cut out Waldo’s location. In order to avoid this, I could have replaced the underlying image all together (as you do not see it at all!) with another image, in which I know where Waldo is. In this case, should you ask me to show you where Waldo is, I will be able to do so, but I will get busted if you selected 1, and made me reveal to you the entire image.

What we got is this:

- If I know where Waldo is, I can deliver a correct answer that you can verify 100% of the time.

- If I am lying and I do not know where Waldo is, you will bust me (no matter what I’ll do) with a probability of at least \(\frac{1}{2}\).

Well, being busted with a probability of only \(\frac{1}{2}\) is not very bad, but notice that we can repeat the process any number of times (each time placing the white papers at different locations over the original image). My chances of being correct are independent in each of the times, and so I will get busted with a probability \((\frac{1}{2})^n\) (where n is the number of iterations). If n is chosen high enough, you can be quite certain that I am not lying (10 iterations suffice for the probability of missing a liar to be less than \(\frac{1}{1000}\)).

Leaking Information

Note that the process is not really “Zero Knowledge” as you do get some information about Waldo’s location. For example, by looking at the cutout version of Waldo you can tell his rotation. This can be easily solved by rotating the base image by a random amount. A bigger problem arises when the papers are not large enough. Indeed, if we repeat this process enough times, you can get some information about the location of Waldo by examining the positions of the cutouts. For example, if waldo is near the center of the original image, you will never be able to get a cutout next to the border. I leave it as an exercise for the reader to mitigate this leak.

More Waldos!

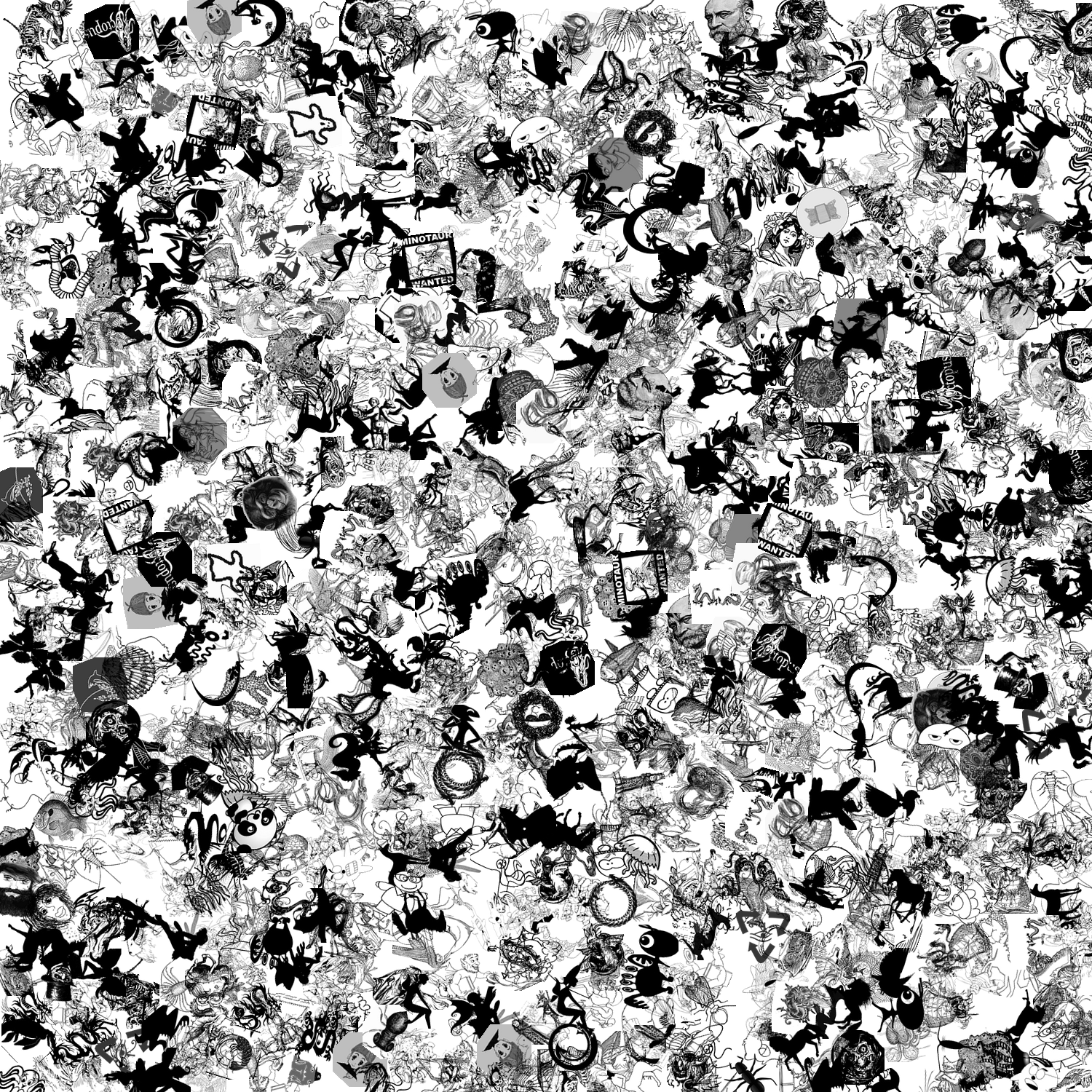

Now for the reason we’re all here - solving some more Where’s Waldo images! I wrote a script that gets a word (e.g. ‘cartoon’) and scrapes publicdomainvectors.org for cliparts of that word and then prepares a Where’s Waldo image from those cliparts. Enjoy!

Where’s Pando?

This is an easier version. This is Pando:

Pando got lost in Cartoon World. Can you find him?

Where’s Baldo?

This is Baldo:

Baldo was walking around Ball World, and got lost! Can you find him?

Where’s Blackdo?

Oh no! Pando got lost again! This time in Monochrome World! Can you find him?

Thanks kids!