Finding the nearest neighbor of a point in a metric space has numerous applications, from machine learning (as a matter of fact, finding the nearest neighbor of an item in feature space is a complete machine learning algorithm! We’ll see a toy example below), to graphics and physics simulation (e.g. I use it extensively in my General Relativity Renderer - I hope to write a post about it soon), or, as we shall see later, for finding the closest word in the dictionary to a given word with spelling mistakes. In this post we will explore a generic data structure for efficiently finding the nearest neighbor of a point in arbitrary metric spaces, and a modern c++ implementation.

A Good Algorithm?

There are several important dimensions that determine how good an algorithm is. Maybe the three most important ones are time complexity, memory complexity, and code complexity. Since in almost all problems you can trade one for one of the others, it’s usually impossible to find a solution that is actually the best, in the sense that it optimizes all three. Once in a while though, you find a nice trade-off, with low time, memory, and code complexities. The solution I’ll describe in this post is one such algorithm, for the problem of efficiently finding the closest point to a target point in a metric space.

An Example Problem

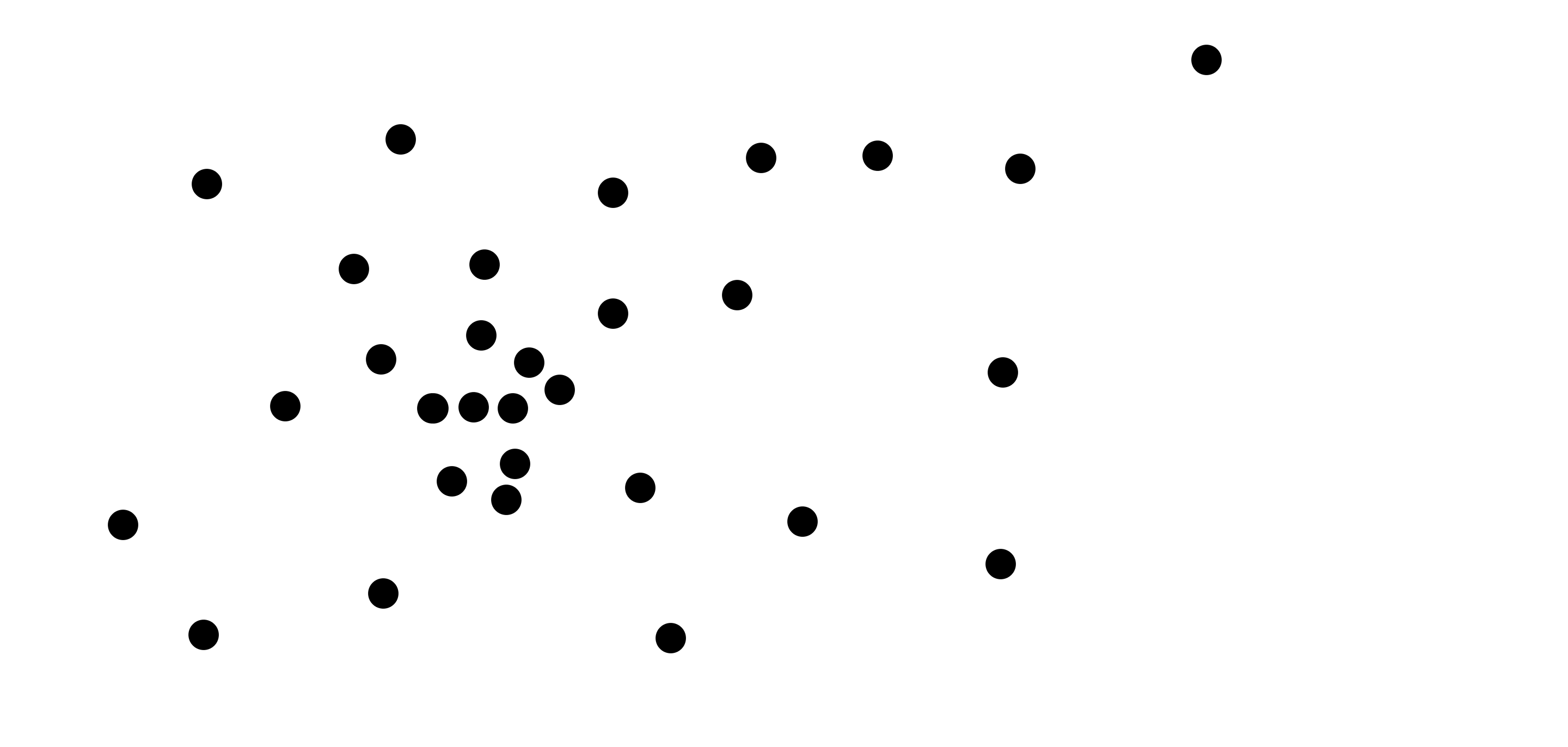

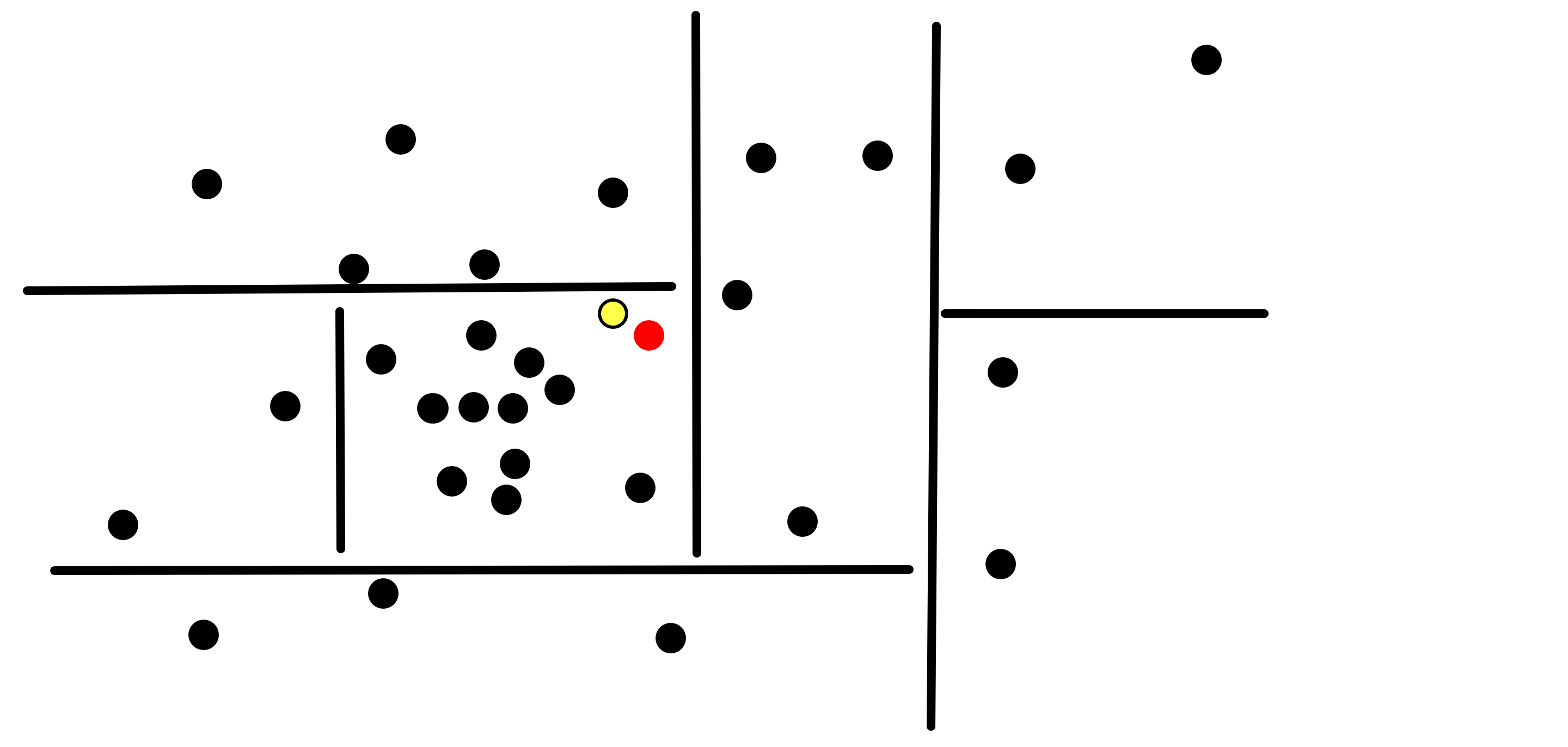

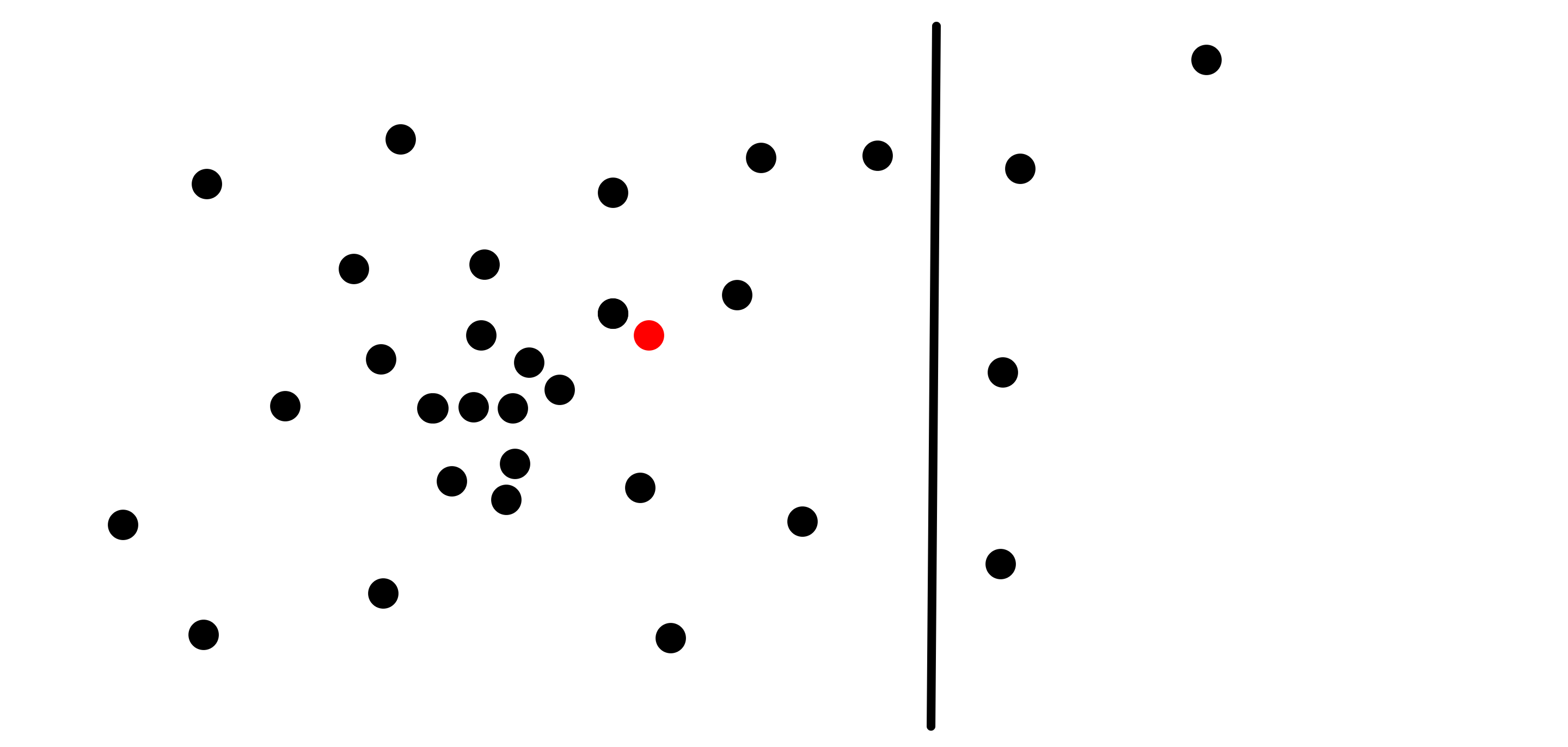

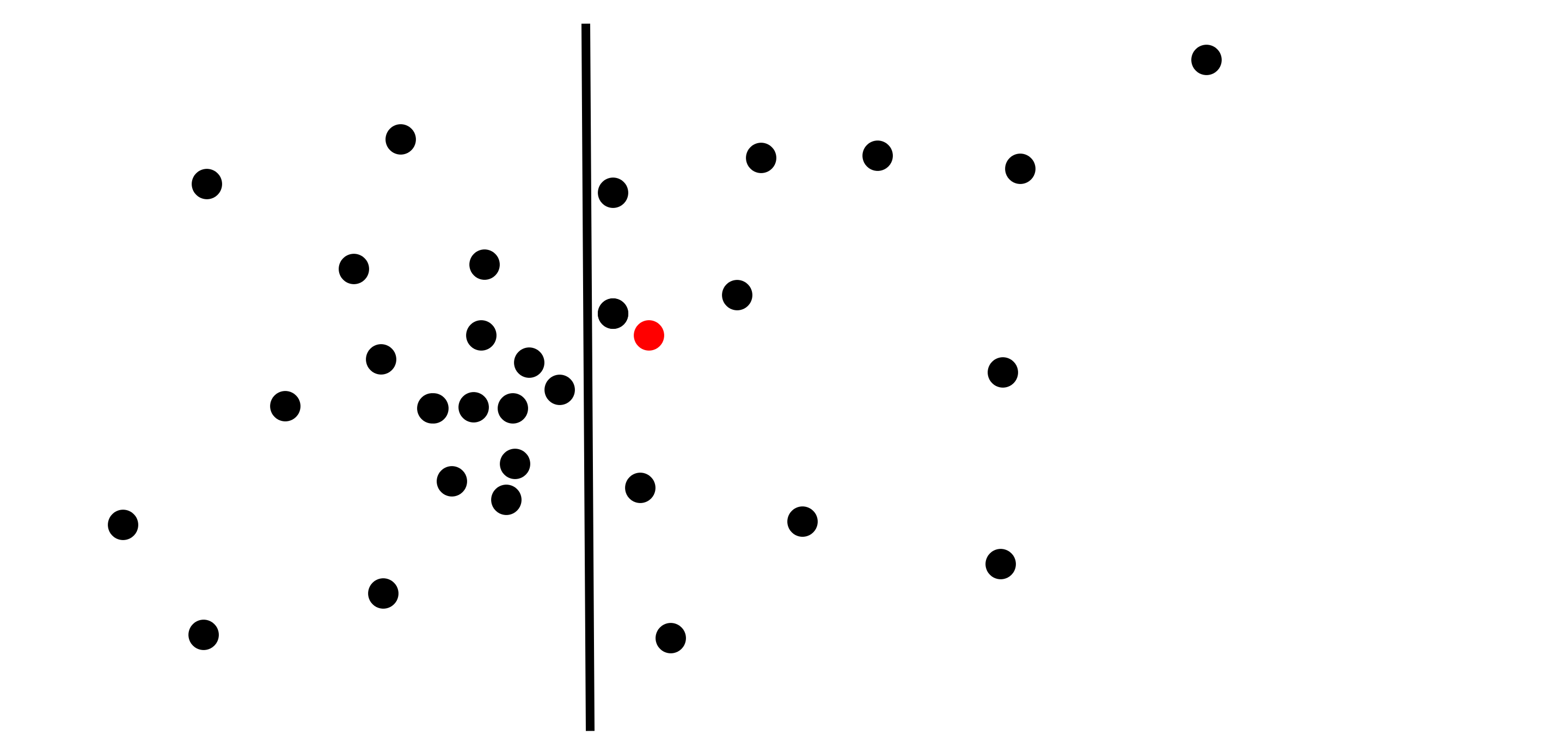

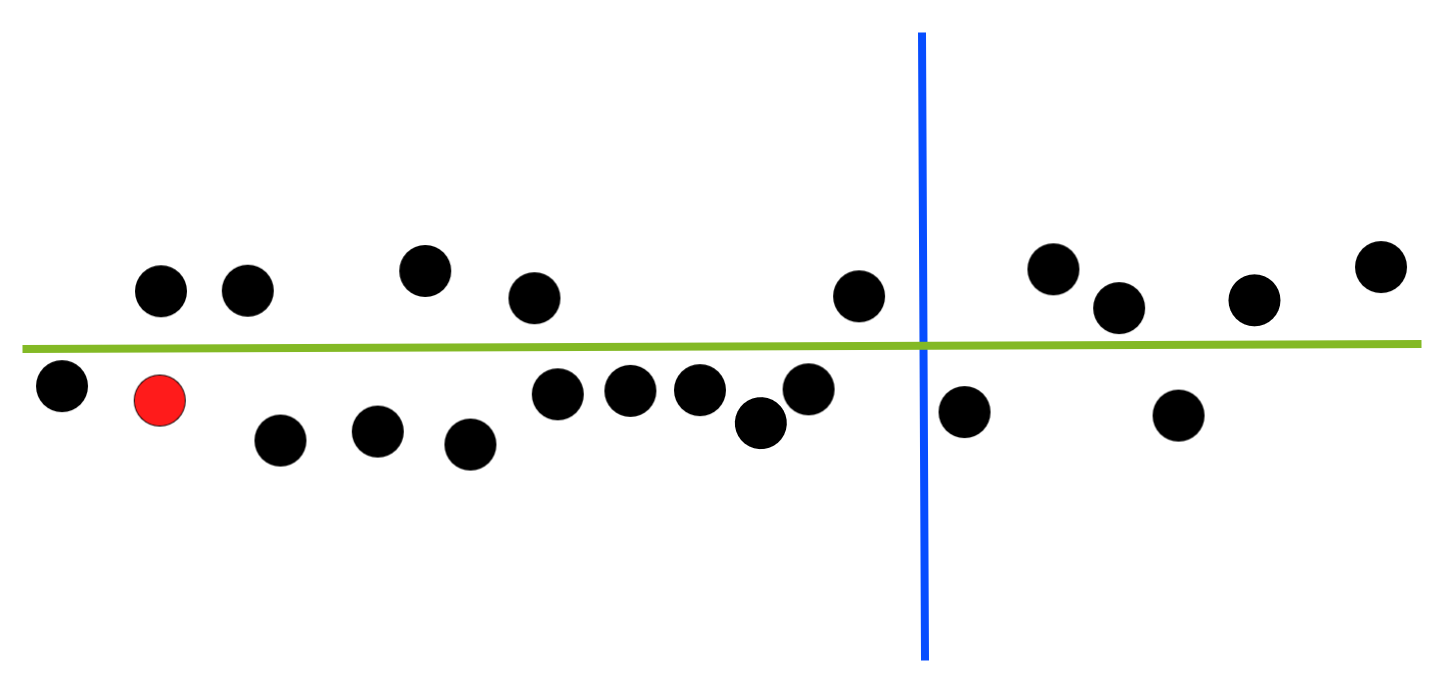

Say we have a set of points in the plane \(R^2\):

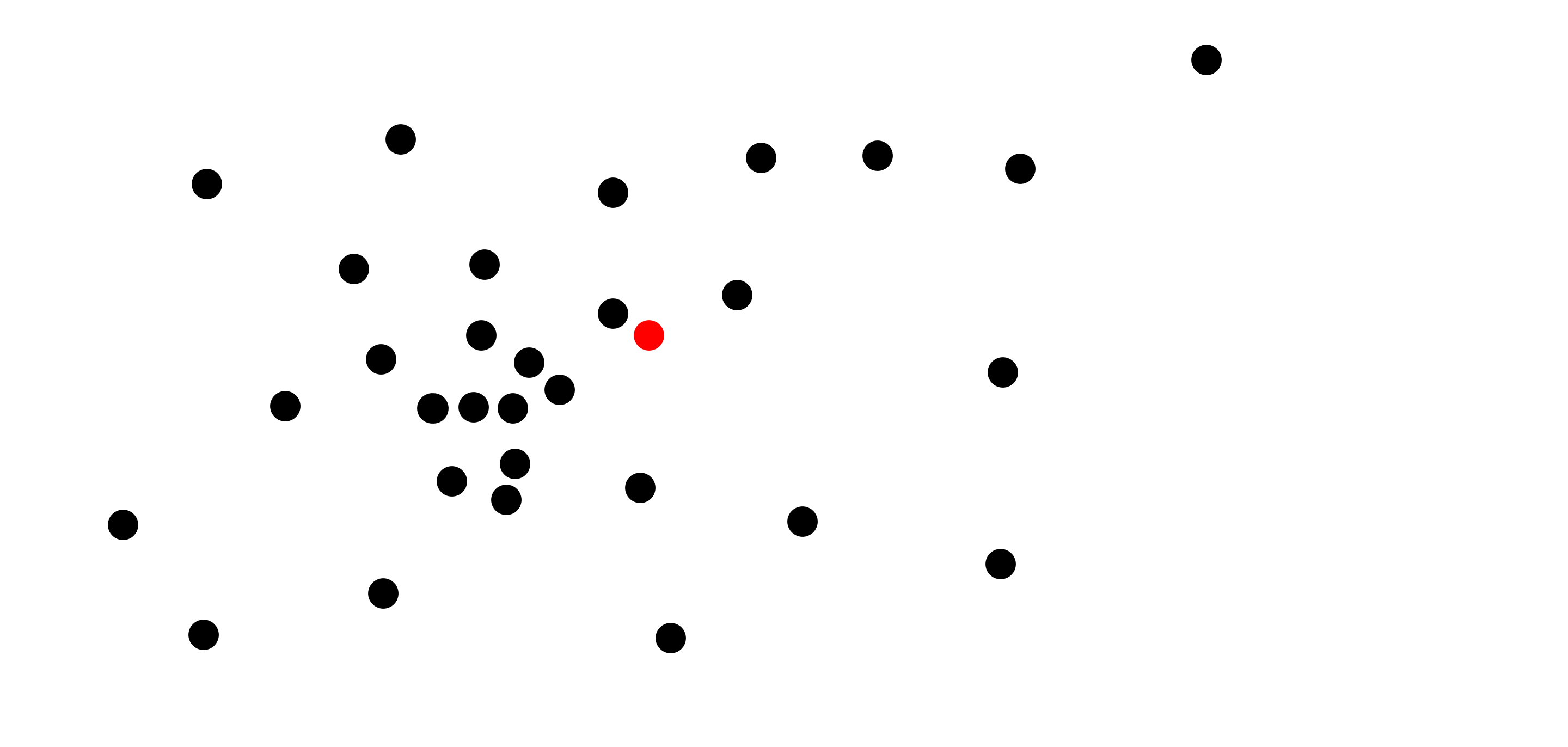

Our goal would be to preprocess them and build a data structure, such that when we get a new target point in the plane (e.g. the red one):

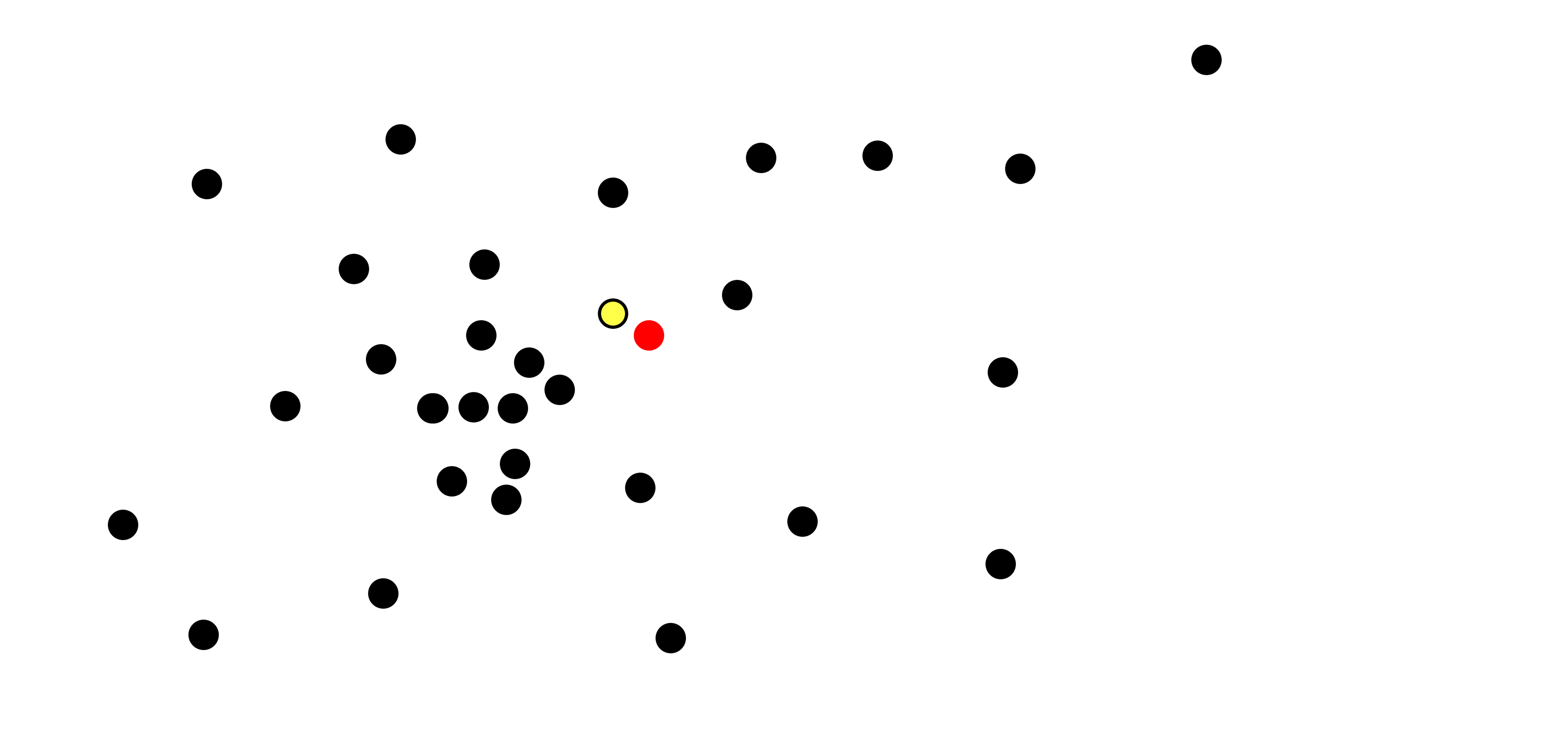

We can efficiently output the closest point from the original set to our target point (e.g. the one with the yellow highlight):

The Standard Solution

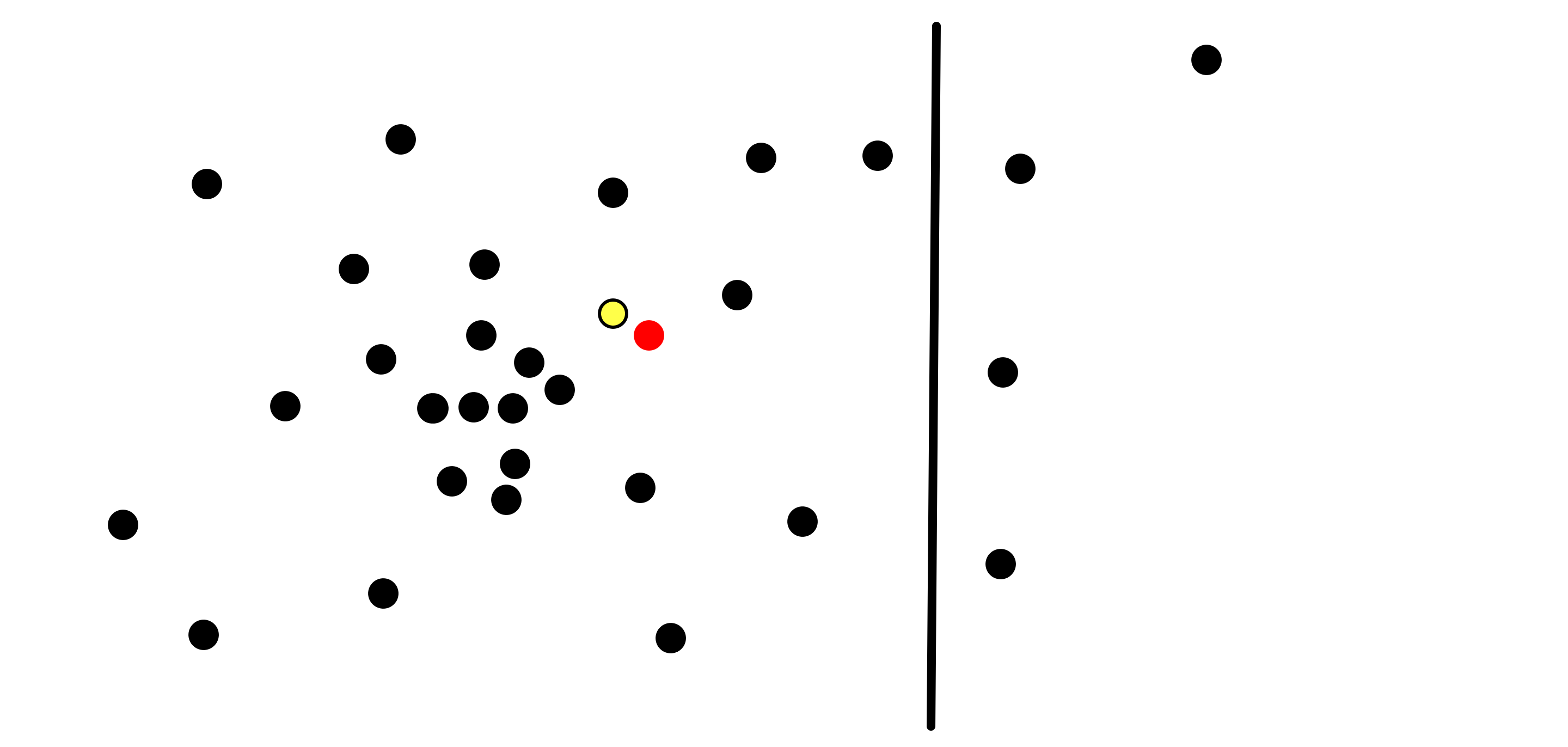

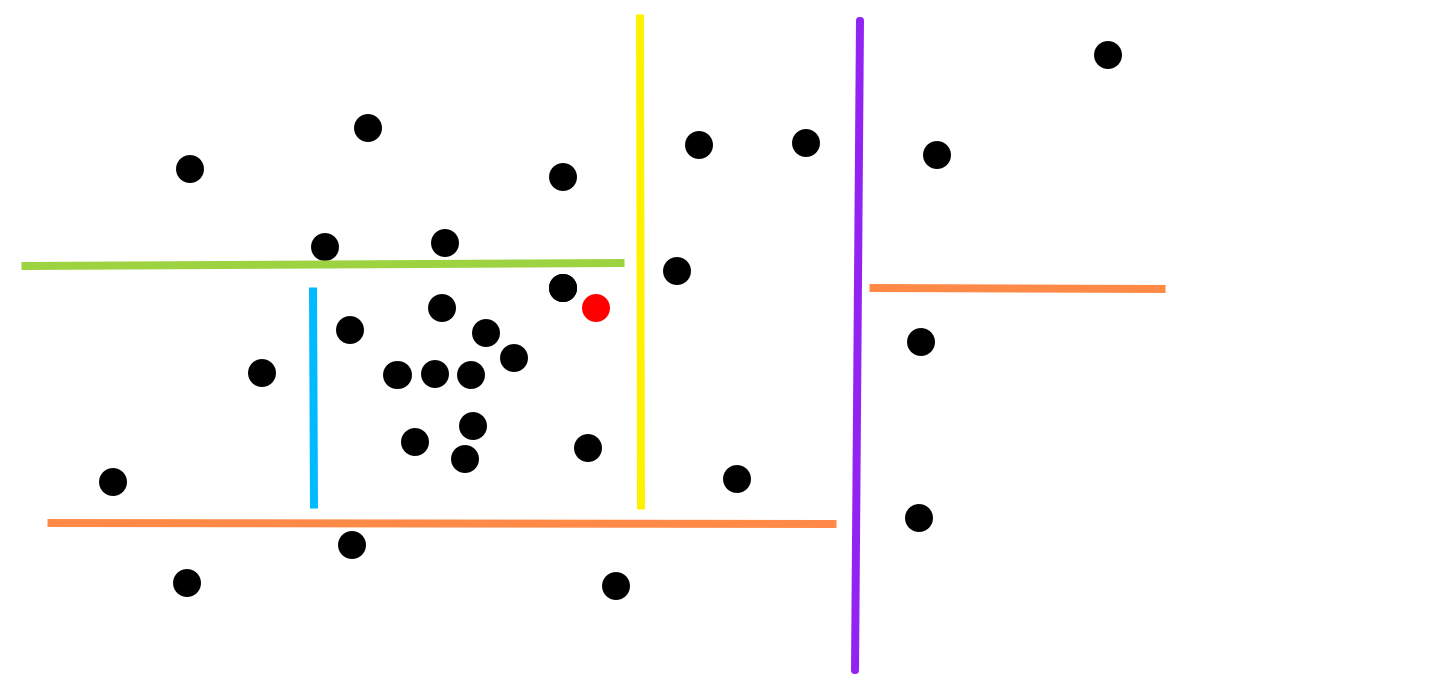

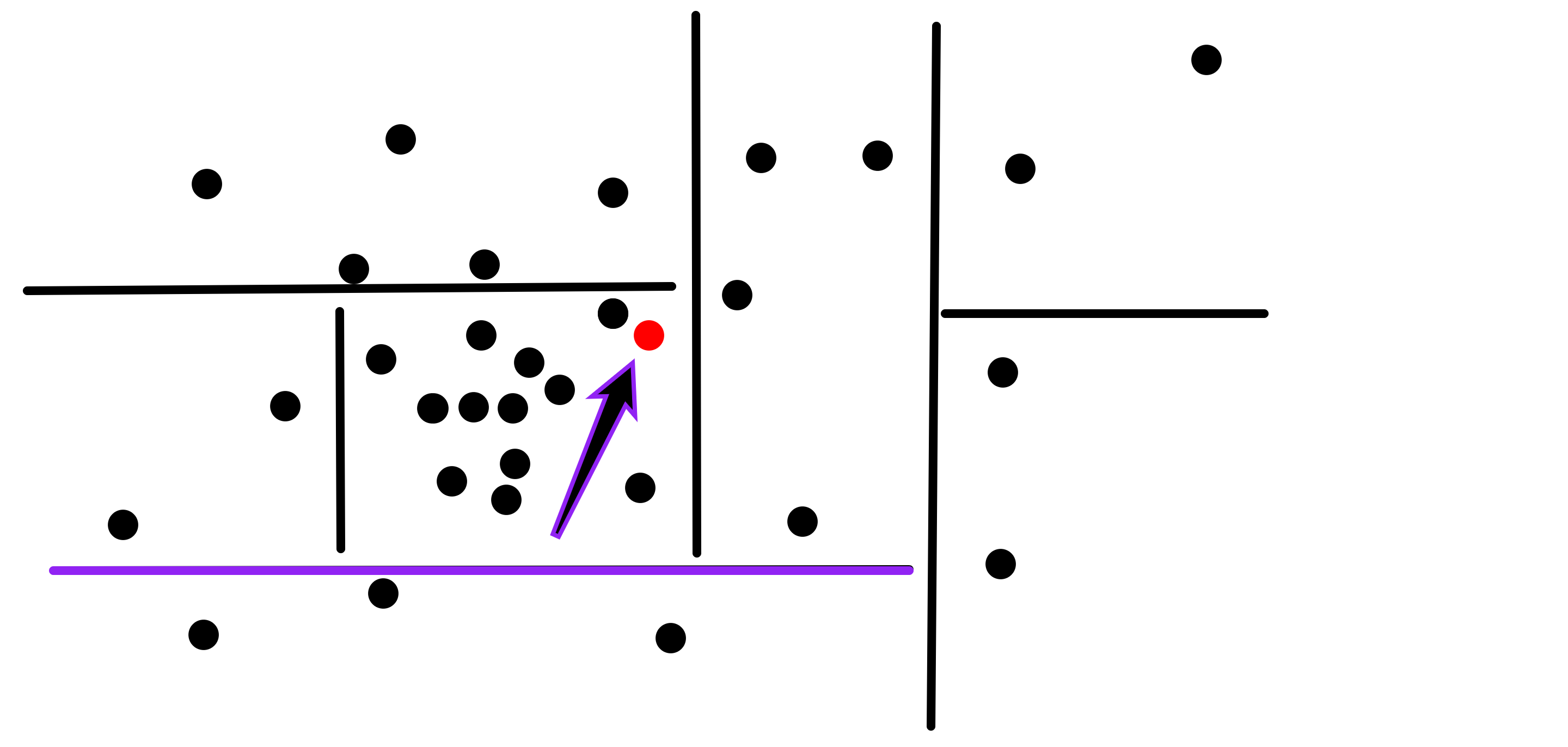

Depending on the parameters of the question, the well-known solutions to this problem are usually things like the k-d tree. A k-d tree is a binary tree, such that each node is associated with a hyperplane that’s orthogonal to one of the axes, and splits the set of points to those on one side of the hyperplane and those on the other side that hyperplane. A hyperplane is simply a plane of dimension one less than that of the space, so in the case of our \(R^2\) example, a hyperplane is just a line:

And here is the same space after we added several such hyperplanes:

For simplicity, we will only deal with axis-aligned hyperplanes, i.e. hyperplanes that are orthogonal to one of the axes, as in the example above.

Note that the above diagram represents a possible k-d tree in \(R^2\), where if a hyperplane is the child of another, we only draw the part of it until it intersects its parent. This specific diagram defines a single k-d tree, as detailed in this diagram:

Here the root hyperplane is purple. Its child hyperlanes orange. One of them has no further children, while the other has a single child - the yellow plane, which has a single child - the green plane, which finally has a last child - the light blue plane. Note though, that while the above diagram defines a unique tree, in general these diagrams are under-specified - i.e. there can be several trees that share the same diagram. Can you see why? (hint - consider what happens if a parent and a child hyperplanes are orthogonal to the same axis, and thus parallel).

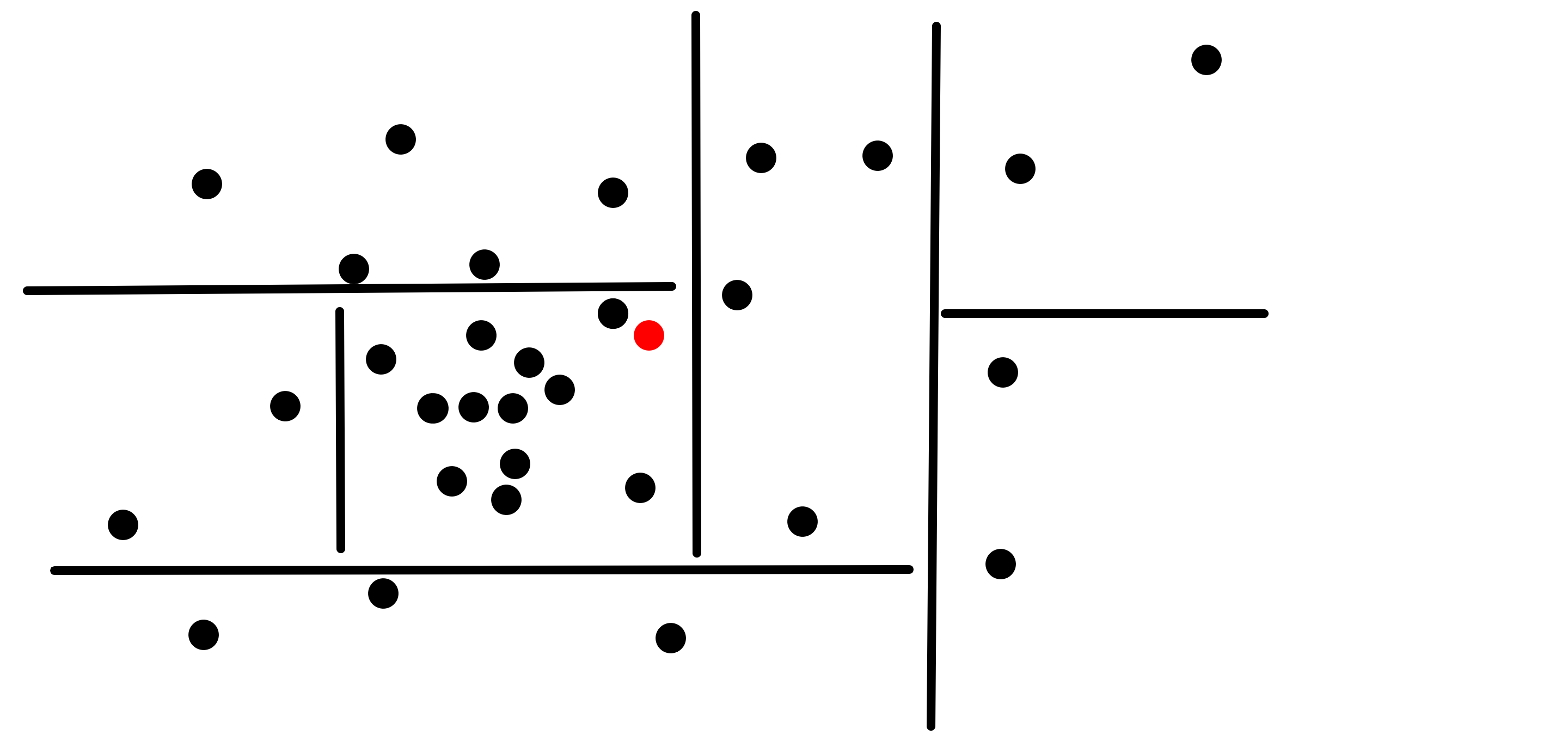

Now when a target point is given, like this red one:

It is first compared to the root node’s hyperplane, and in this case it is determined that it is on its left side:

It is then recursively searched on the left side, comparing it to the root node’s left child’s hyperplane, here determined to be above it:

Now, you might say:

Wait, I see where this is going - you want to do a binary search and only examine the branch of the tree that contains our target point - but there is a problem! We still need to check the other side of all the hyperplanes! It’s possible that a point is to one side of a hyperplane, but the closest point to it is on the other side!

You’d be very right in saying so, as this diagram depicts:

So is all hope lost? Do we need to check the entire tree, and lose the logarithmic complexity? No! Note that due to the triangle inequality, all the points on the other side of the plane from a point are farther away from the point than the plane. In other words, we only need to check the child node not containing our target point, if we already checked the child node that does contain it, and the closest point that we found is farther away from the target point than the separating hyperplane. This gives us hope that we might see logarithmic complexity with the k-d tree algorithm.

Here is the above in pseudo-code:

def find(tree, target):

if tree.isLeaf(): return tree.point

subtree_with_point, other_subtree = tree.get_subtree_with_point(target)

closest = find(subtree_with_point, target)

if distance(closest, target) < distance(closest, tree.hyperplane):

return closest

closest2 = find(other_subtree, target)

if distance(closest, target) < distance(closest2, target):

return closest

return closest2

Optimizations

Multiple Points Per Leaf

One standard and simple optimization, is that instead of storing only a single point at each of the leafs, we can choose to store a vector of points of some length at each leaf. We would then stop constructing child nodes when a leaf has that number of points or less. The adjustment to the pseudo-code above is trivial, we would just change one line:

if tree.isLeaf(): return tree.point

To:

if tree.isLeaf(): return closestPointInList(tree.points, target)

See the Benchmarking section below for some results of how this number affects the performance.

Choosing the Hyperplanes

A much more important optimization comes from the way we choose the hyperplanes. So how should we chose which hyperplanes to use?

Good Hyperplanes

Let’s consider two desirable traits for the chosen hyperplanes:

- We’d like the hyperplane to split the points as evenly as possible, to minimize the worst case depth.

- We’d like the points on each side of the hyperplane to be as far away as possible from the hyperplane. This criteria is important, as even if the tree has logarithmic depth, if the find algorithm above needs to explore both sides of the hyperplane often, it might run for more than a logarithmic number of steps.

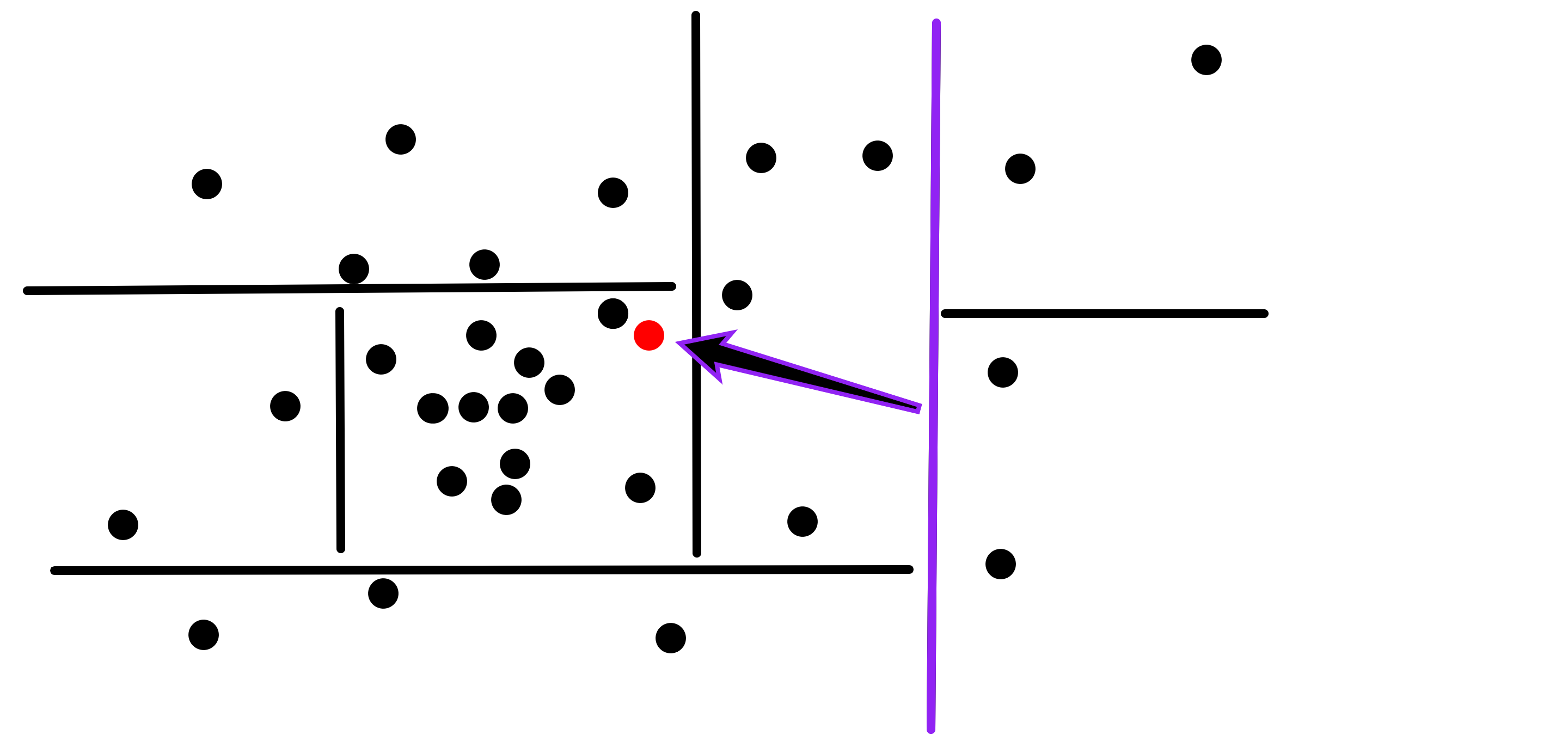

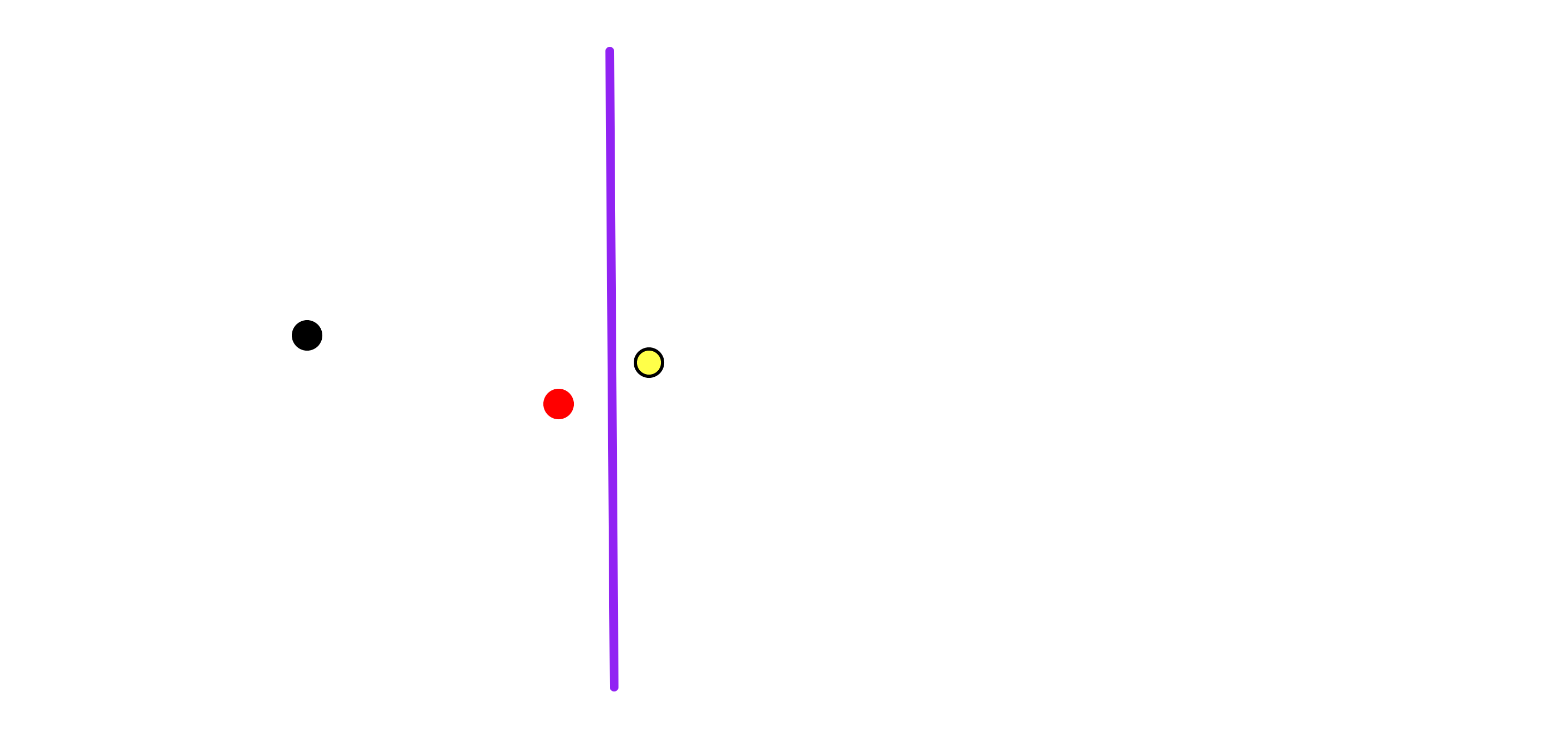

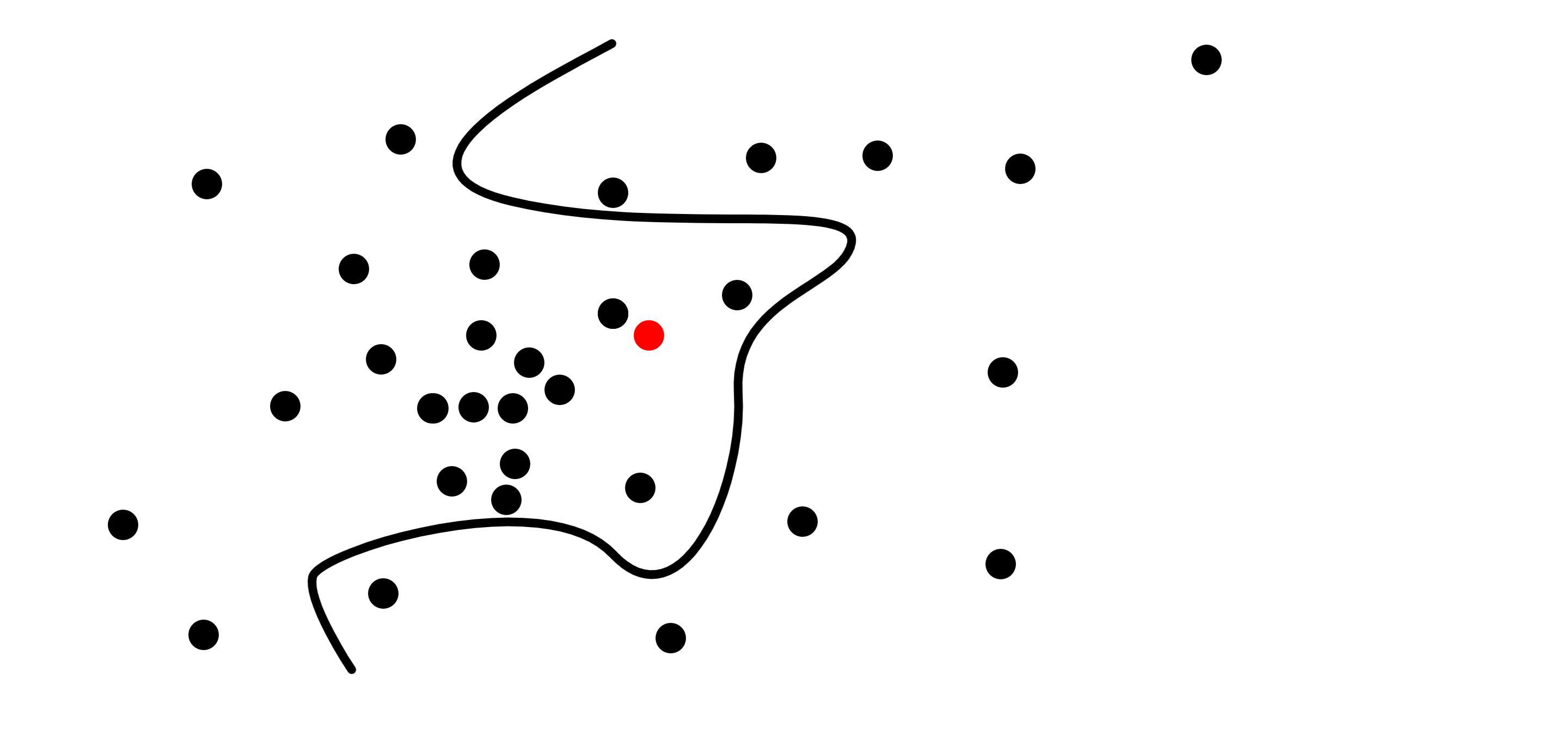

For example, the root hyperplane in the example above is chosen poorly as very few points lie to its right, violating desirability trait #1:

While this one seems better:

What about criteria #2? Consider the blue and the green hyperplanes in this diagram:

While the green line separates the points more evenly (so is better according to criteria #1), according to criteria #2, the blue line is better. Indeed, if we are trying to find the nearest neighbor for a point with a similar distribution to that of the original set of points, e.g. the red target point, we are likely to need to check both sides of the green hyperplane, whereas we are likely to only need to check one side of the blue hyperplane.

Degrees of Freedom

When choosing axis-aligned hyperplanes there are two things we are actually choosing:

- Which axis the hyperplane will be perpendicular to (\(X\), \(Y\), or \(Z\))?

- What is the point of intersection of the hyperplane and that perpendicular axis?

We have several ways for choosing both. For #1, we could, at every node choose randomly between the axes, or we could choose in a round-robin fashion, or we could always choose the same axis (this one doesn’t sound very promising), or we could choose based on a criteria that depends on the actual points (e.g. take the axis upon which the projection of the points in the child has the largest difference between the minimum and maximum, or the axis with the highest entropy, etc.). See the benchmarking section below for experiment results with many of these.

Once we chose the axis, we need to choose the intersection point. Here again we can employ several strategies: we can choose a random point from the set and take its projection on the axis as the intersection point, or we can choose the median point’s projection instead of a random point (sounds more promising). Here too, see the benchmarking section below for experiment results with a couple of these.

Non Binary Trees

Another simple optimization (which we won’t implement) is to consider a set of k hyperplanes (say parallel to each other) at each of the nodes of the tree. Instead of just considering on which side of a single hyperplane an item is, we’d then need to determine between which two hyperplanes an item is. While adding support for this is trivial, the reason we won’t be doing this is that it gets much more hairy if we want to support volume - which we do. Let’s see what that means.

Supporting Volume

We discussed above supporting multiple points per leaf, instead of just a single point per leaf. Once we implement that, we can trivially add a really cool feature, that I found useful in several application: supporting spheres instead of points. Specifically, we want to allow each item that we insert to the tree to have a potentially non-zero radius. In order to enable that, it is enough to allow all nodes in the tree to contain items, not just the leafs, and whenever we add an item to the tree, if its sphere intersects the hyperplane (basically meaning it is both to the left and to the right of it) we simply keep it in the parent node, instead of in the child nodes.

Beyond Hyperplanes

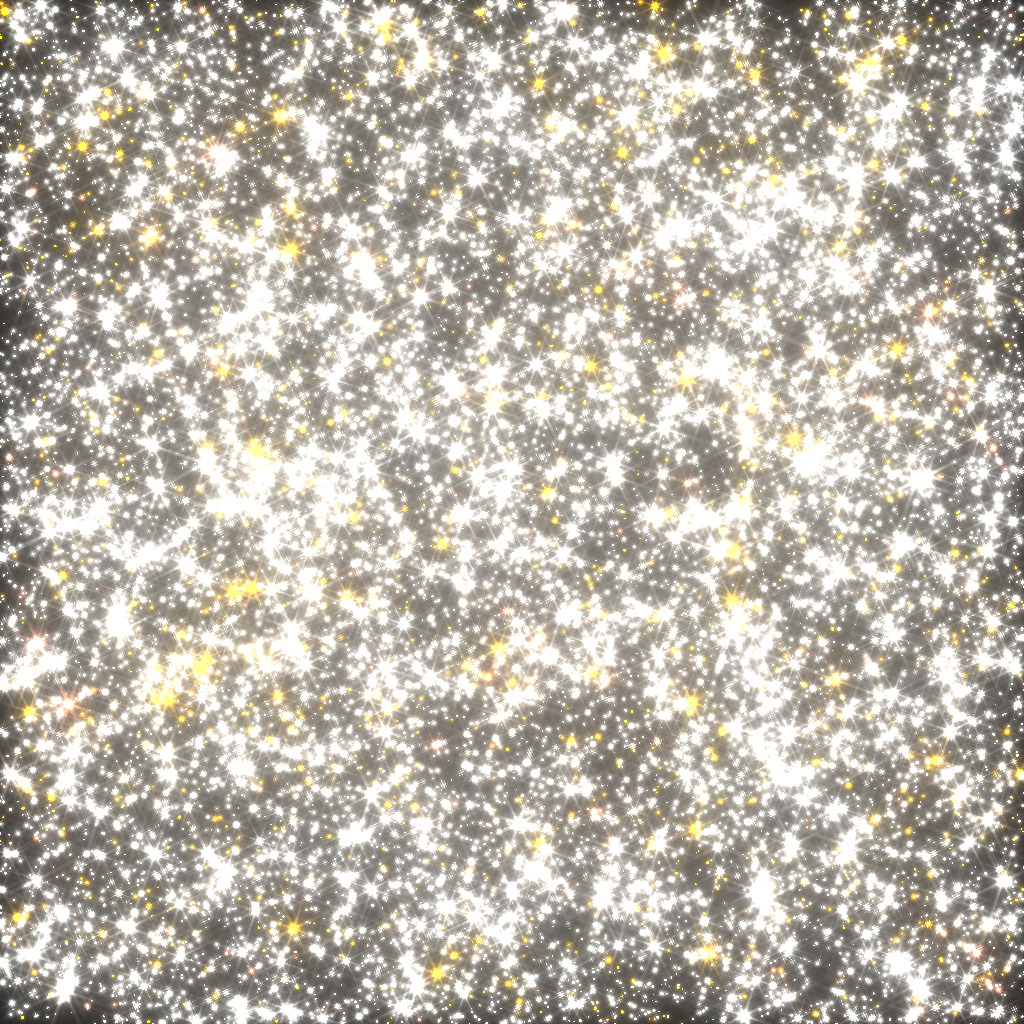

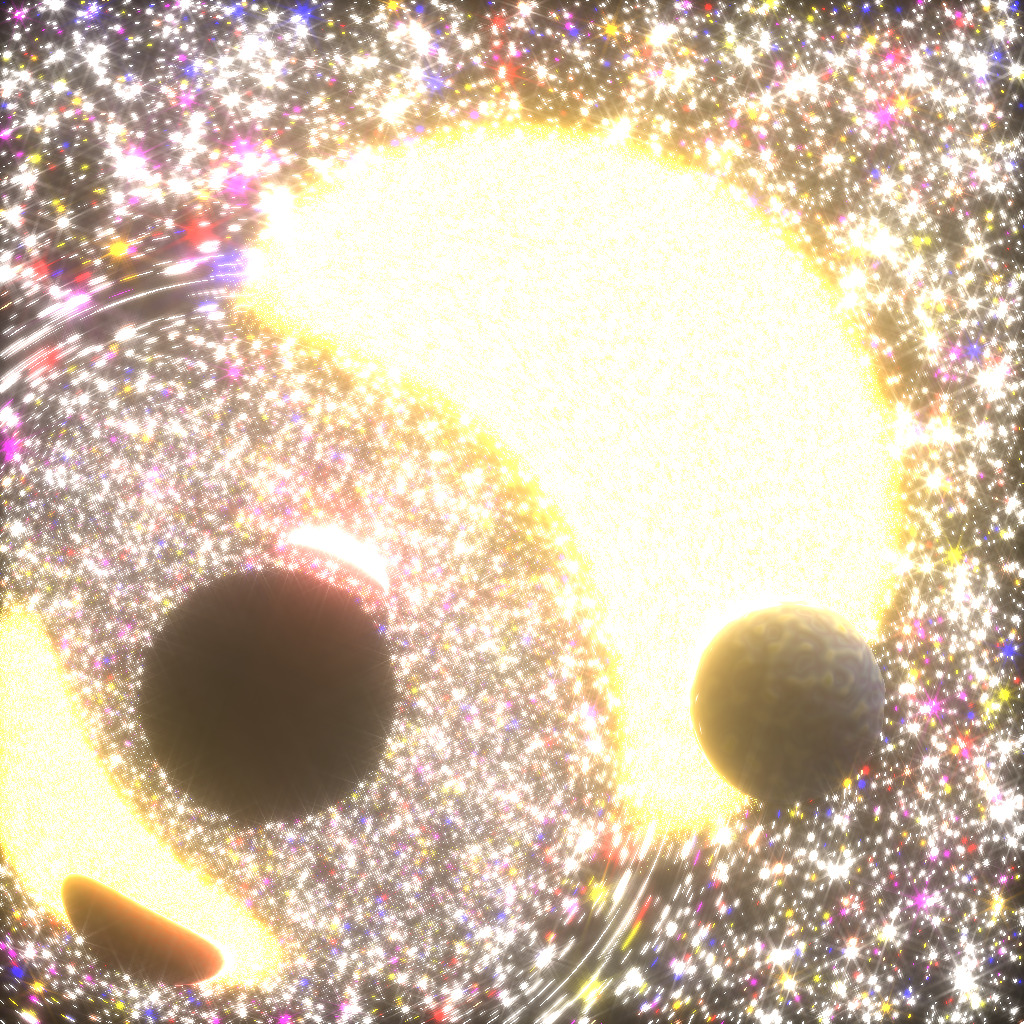

I got to program k-d trees several times for various projects, for example, for my General Relativity Renderer, I needed to detect the collision of light photons with millions of stars, and storing them in a k-d tree enabled rendering such images as this one:

I will write a full post about that project at some point.

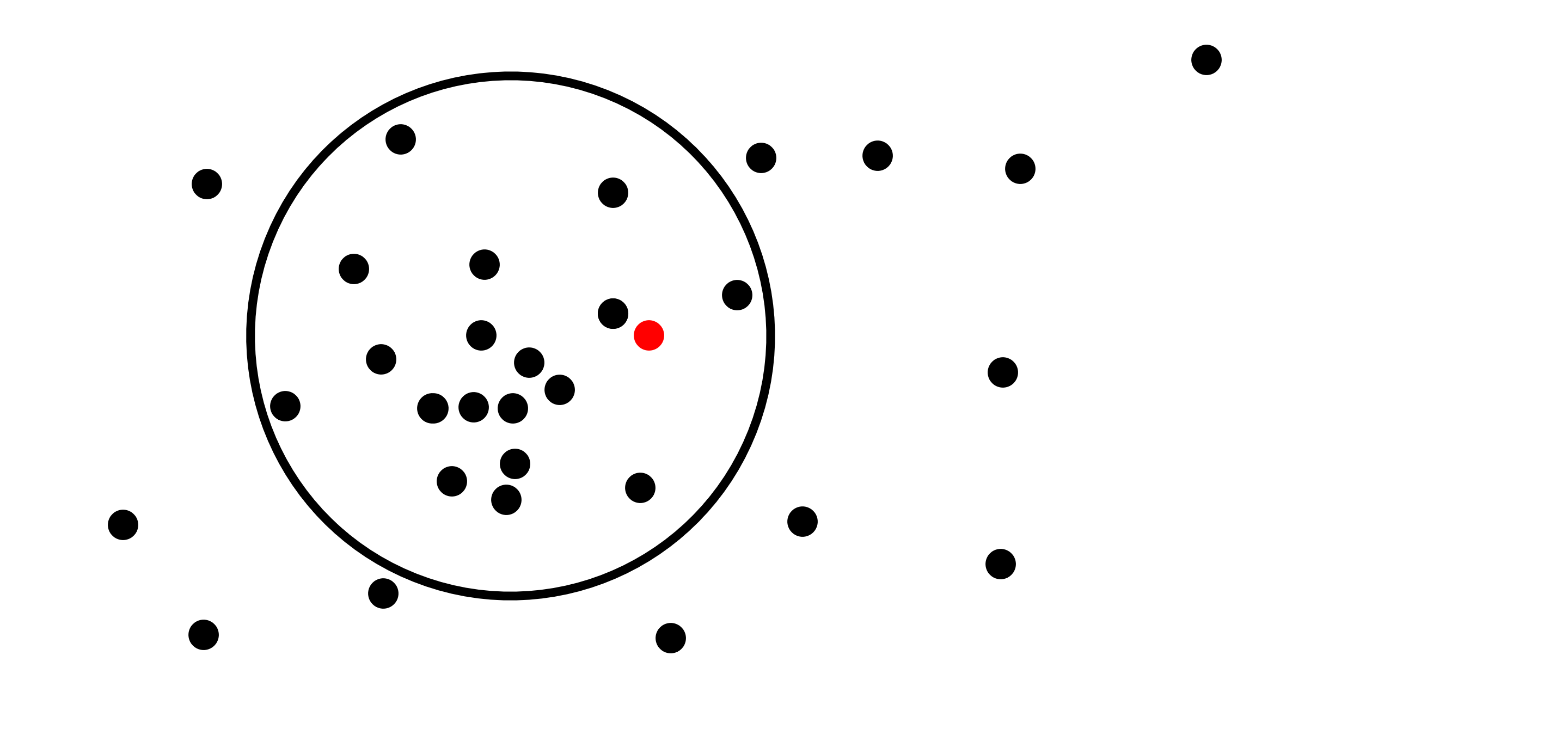

What I realized recently, and one of the coolest things imo in this post, is that there is a lot of arbitrariness in the fact that we’re using axis-aligned hyperplanes for the k-d tree, in fact, there is a lot of arbitrariness in using hyperplanes altogether - we can actually use any hypersurface. For example:

Hyperplanes, and specifically axis-aligned hyperplanes have the huge benefit that it is very easy to calculate to which side of them a point lies and the distance between them to the point. And while this might be hard to do for arbitrary hypersurfaces, for some hypersufaces this is easy. For example, it’s super easy to calculate both of the above for spheres:

Taking this idea one step further, there is even arbitrariness in requiring a Euclidean space at all. Really what the above reasoning relies on is simply the properties of a metric space. The triangle-inequality implies that all the points on the other side of a hypersurface from a point are farther away from the point than the hypersurface. Recall that the distance of a point from a hypersurface is just:

\[D(p, s) = \min\{|x-p| \mid x \in s\}\]Nit note: since we are dealing with closed hypersurfaces in \(R^n\), the formula above actually gets its minimum value.

Taking a step back - we can actually get the above data structure to work without mapping the items to points in some Euclidean space, but rather keeping them in an arbitrary metric space!

For example, note that the Levenshtein distance satisfies all the requirements for being a metric:

- \[d(s1, s2) \ge 0\]

- \[d(s1, s2) = 0 \Leftrightarrow s1 = s2\]

- \[d(s1, s2) = d(s2, s1)\]

- \[d(s1, s2) + d(s2, s3) \le d(s1, s3) \\ \text{(triangle inequality)}\]

So we could use this same spatial partitioning data structure (it’s no longer a k-d tree really) to index all the words in the dictionary and efficiently find the closest word to a given word with potential spelling errors!

Of course in a general metric space, the notions of axes and hyperplanes don’t exist, so we can’t use them as our hypersurfaces. But we can still use spheres!

Gist of the Code

While the full implementation is pretty concise (you can find it at the end of the post), I wanted to give here just the gist of the code including just the most important parts:

// A hyperplane in R3 perpendicular to one of the Axes.

struct AxisAlignedHyperplane {

vec3::Axis perpendicular_axis = vec3::X;

float intersection_coord;

};

template <class ValueType>

struct SphereHypersurface {

ValueType center;

float radius;

};

template <class ValueType = vec3, class Hypersurface = AxisAlignedHyperplane,

class HypersurfaceSelector = AxisAlignedHyperplaneSelector<

ValueType, RoundRobinAxisSelector<ValueType>>,

DistanceFunc<ValueType> Distance = dist,

class MaxSplit = SplitSize<32>>

class Tree {

public:

void compile(const HypersurfaceSelector& hypersurface_selector =

HypersurfaceSelector()) {

if (items.size() <= MaxSplit::size) return;

hypersurface = hypersurface_selector.selectHypersurface(items);

splitItemsToChildren();

if (_children[0] != 0) {

_children[0]->compile(hypersurface_selector.child());

}

if (_children[1] != 0) {

_children[1]->compile(hypersurface_selector.child());

}

}

void splitItemsToChildren() {

std::vector<ValueType> all_items;

std::swap(items, all_items);

for (const ValueType& item : all_items) {

RelationToHypersurface item_to_hypersurface =

relation(*hypersurface, item);

if (item_to_hypersurface.intersects()) {

items.push_back(item);

} else {

child(item_to_hypersurface.side())->add(item);

}

}

}

ItemWithDistance findClosest(const ValueType& target) const {

ItemWithDistance res;

for (const ValueType& item : items) {

float distance = std::max<float>(0, Distance(item, target));

res = ItemWithDistance::min(res, ItemWithDistance{item, distance});

if (res.distance == 0) return res;

}

if (!isLeaf()) {

RelationToHypersurface target_to_hypersurface =

relation(*hypersurface, target);

Tree* child_with_target = _children[target_to_hypersurface.side()].get();

if (child_with_target) {

res =

ItemWithDistance::min(res, child_with_target->findClosest(target));

if (res.distance == 0) return res;

}

Tree* child_without_target =

_children[target_to_hypersurface.otherSide()].get();

if (child_without_target &&

target_to_hypersurface.distance() < res.distance) {

res = ItemWithDistance::min(res,

child_without_target->findClosest(target));

}

}

return res;

}

private:

std::vector<ValueType> items;

std::optional<Hypersurface> hypersurface;

std::unique_ptr<Tree> _children[2];

};

So how would this be used? Here’s an example (see the full implementation below for the details):

spatial_partition::Vec3KDTree tree;

tree.fromVector(vector_of_vec3s);

vec3 target = ...;

vec3 closest = tree.findClosest(target);

And how about using it for finding the closest string from a dictionary?

std::vector<std::string> words;

LoadWordsFromDictionary(&words);

spatial_partition::StringVPTree tree;

tree.fromVector(words);

tree_closest = tree.findClosest("Yaniv").item;

std::cerr << "The closest word in the dictionary to 'Yaniv' is: " << tree_closest << std::endl;

Toy Example - Machine Learning a COVID Detector

Before we start with serious benchmarks, let’s use our spatial data structure to build a simple machine learned model to detect whether someone has COVID. The features we’ll use are the person’s body temperature, the number of times the person coughs in a day, and a completely irrelevant feature of the person’s favorite number. We’ll generate some random data for these features like so:

- If a person is healthy, we’ll assume that their body temperature is normally distributed with a mean of 98.6°F and a standard deviation of 0.45°F. For a sick person we’ll assume the same standard deviation but a mean of 1°F higher.

- We’ll assume that the number of times a healthy human coughs in a day is geometrically distributed with a parameter of 0.5. The parameter we’ll use for a sick person will be 0.25.

- Finally we’ll let everyone’s favorite number be an integer uniformly distributed between 1 and 100, regardless of whether a person is sick or not (we should really have given 17 a higher chance…).

Here’s all of that in code:

struct Example {

vec3 features;

enum Label { Healthy = 0, Sick = 1 } label;

};

Example getRandomHealthy() {

std::normal_distribution<double> temperature(98.6, 0.45);

std::geometric_distribution<int> coughs_per_hours(0.5);

std::uniform_int_distribution<double> favorite_number(1, 100);

return Example{vec3(temperature(generator), coughs_per_hours(generator),

favorite_number(generator)),

Example::Healthy};

}

Example getRandomSick() {

std::normal_distribution<double> temperature(98.6 + 1, 0.45);

std::geometric_distribution<int> coughs_per_hours(0.25);

std::uniform_int_distribution<double> favorite_number(1, 100);

return Example{vec3(temperature(generator), coughs_per_hours(generator),

favorite_number(generator)),

Example::Sick};

}

And here is our toy machine learning model:

struct NearestNeighbor {

spatial_partition::KDTree<Example, dist> tree;

void train(const std::vector<Example>& training_data) {

tree.fromVector(training_data);

}

int classify(const Example& example) { return tree.findClosest(example).item.type; }

float eval(std::vector<Example>& eval_set) {

int correct = 0;

for (const Point& example : eval_set) {

if (classify(example) == example.type) {

correct++;

}

}

return float(correct) / eval_set.size();

}

};

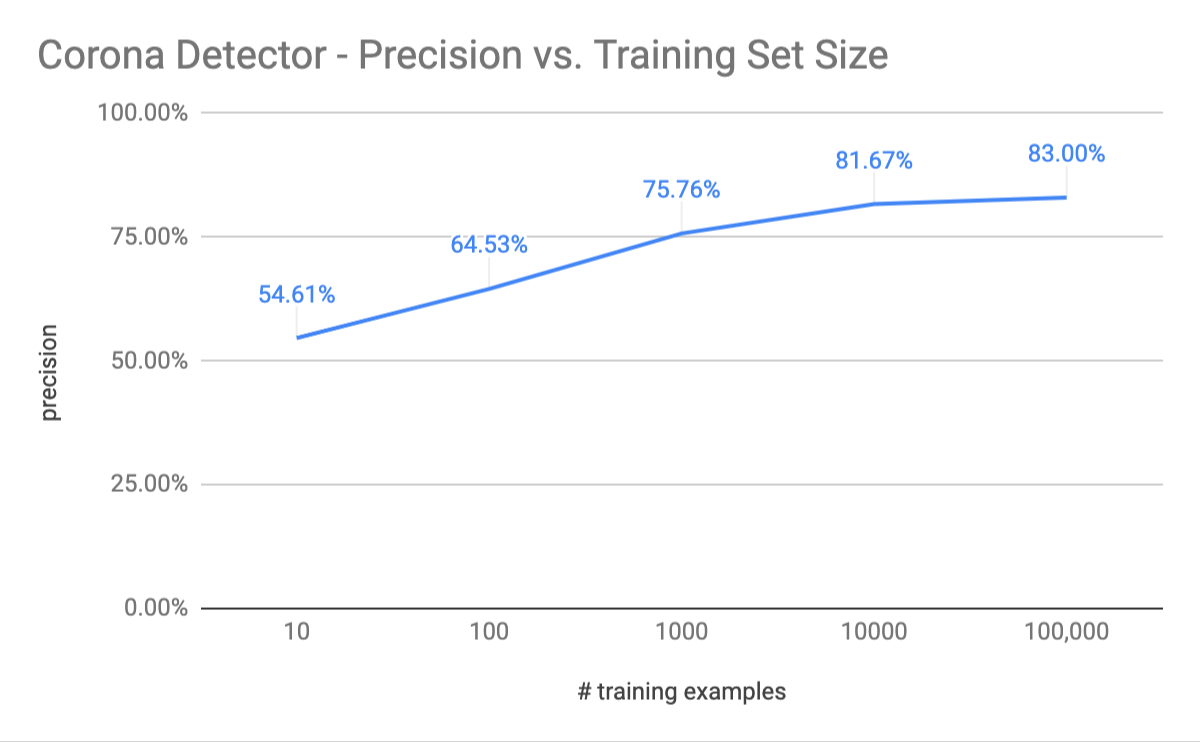

And that’s it! So how well does this perform? Running this with a training set of just 10 examples, gives us just a slightly-better-than-random predictor with a correct prediction only about 55% of the time. This isn’t too surprising as we’re completely thrown off by the favorite number, that is large in magnitude, compared to the other features (it might be a good idea to normalize all the features, but that’s a topic for a different post). Increasing the training size to 100 samples, the model already predicts correctly around 65% of the time. With 1,000 samples, the model gets it right around 76% of the time. With 10,000 samples, the model predicts correctly around 82% of the time! Not too shabby for just a couple of lines of code!

The model’s precision looks to saturate around the 8X% precision (with 100,000 training examples we get a precision of 83%). As an exercise for the reader, what is the theoretical maximal precision, of the ideal machine learned model on this data set?

Benchmarking

So how does this implementation compare to trivial baselines (of basically just iterating over the data and taking the closest point, with only minor optimizations, like bailing early as soon as a point of distance 0 is found)? For practical applications, where indeed finding the closest point is the bottleneck, the above code can be much further optimized. That said, most optimizations would require hurting the complexity of the code. As it turns out, this implementation already performs orders of magnitude better than the trivial approach (at least in the Euclidean case).

Results

Trees in Euclidean Spaces

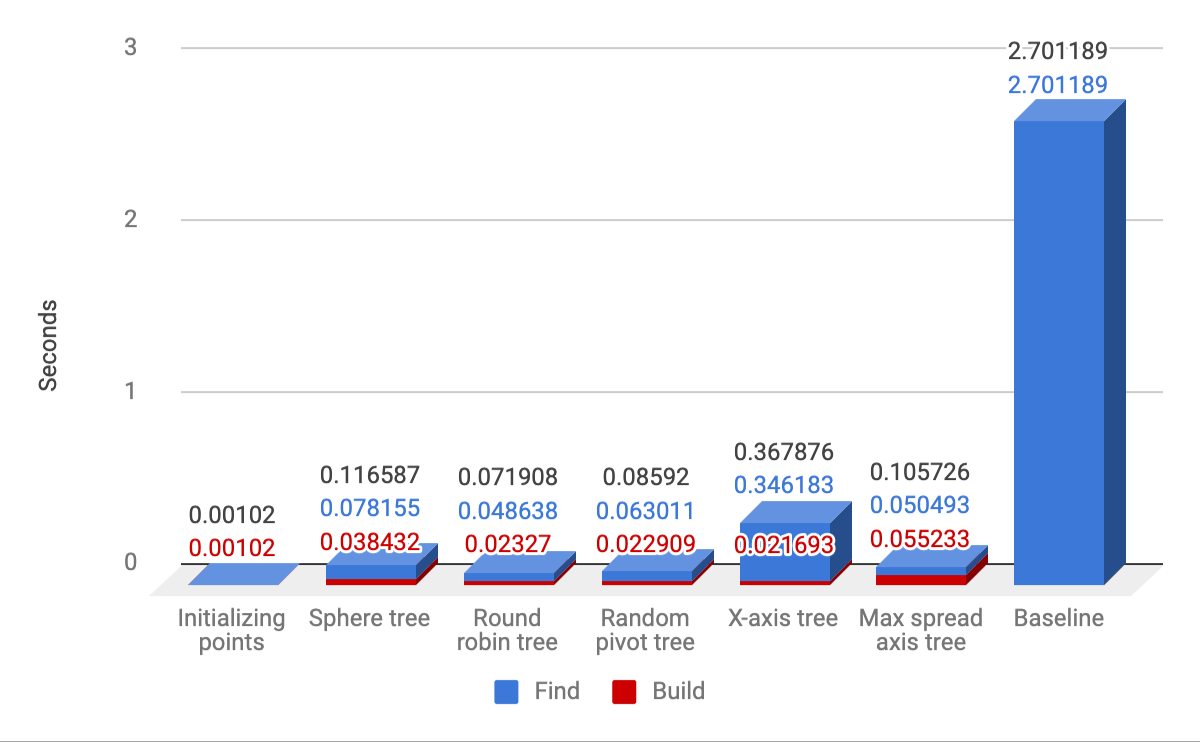

So here are the results for indexing 10,000 points in \(R^3\) and performing 10,000 finds:

For calibration, on my setup, creating the 10,000 random vec3s took 0.001 seconds (or 1 milli second). The rest of the columns represent several tree configurations. The number in red is the cost of building the tree, and the number in blue is the cost of performing the 10K find-closest operations. The baseline algorithm, has 0 build cost, and takes 2.7 seconds to perform 10K find-closest operations. The best performing tree in this setup is the round-robin axis aligned tree, with a total cost of 0.07 seconds for the 10K operations (including the building time). Building it costs only 2.3 milliseconds. The random-pivot tree and the max-spread tree perform very similarly. Interestingly, the sphere-tree (that completely ignores the fact that the points are in a Euclidean space) and chooses random pivots, performs really well - less than twice as bad as the round-robin tree. Also, interestingly, the x-axis only tree (which basically ignores the y and z coordinates completely and just binary-sorts all the points according to their X-coordinate) performs much worse than all of the other tree configurations, but still about an order of magnitude better than the baseline approach (0.36 seconds vs 2.7 seconds for the baseline approach).

A Larger Data Set

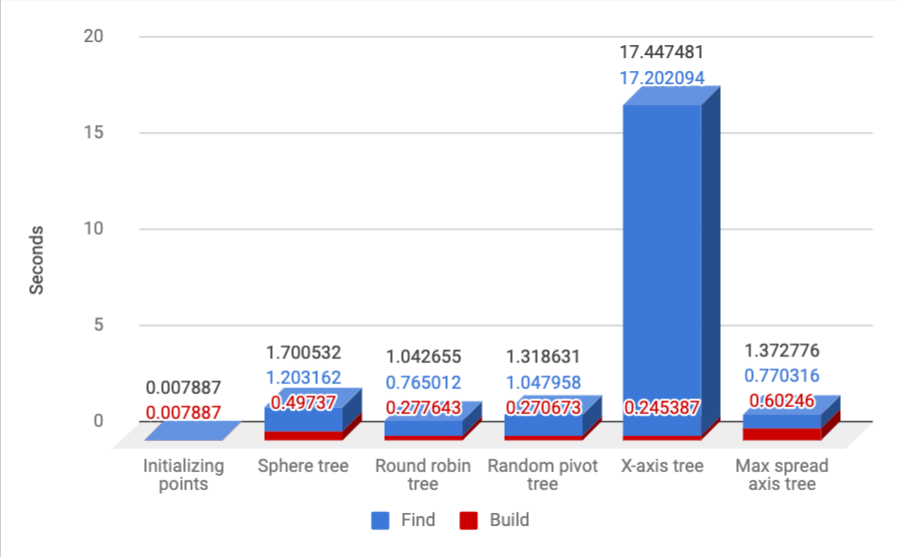

What happens on an even larger data set? Here we see the results for 100,000 points in \(R^3\) and 100,000 finds. The baseline would have been way too slow for this one (estimated at around 5 minutes - more than I have patience for :)) so I am not including it:

Here too it’s easy to see that the round-robin method dominates, with very fast build time, and the best find time. It is able to build the tree and perform the 100K find-closest operations in just over a second.

A Different Distribution of Points

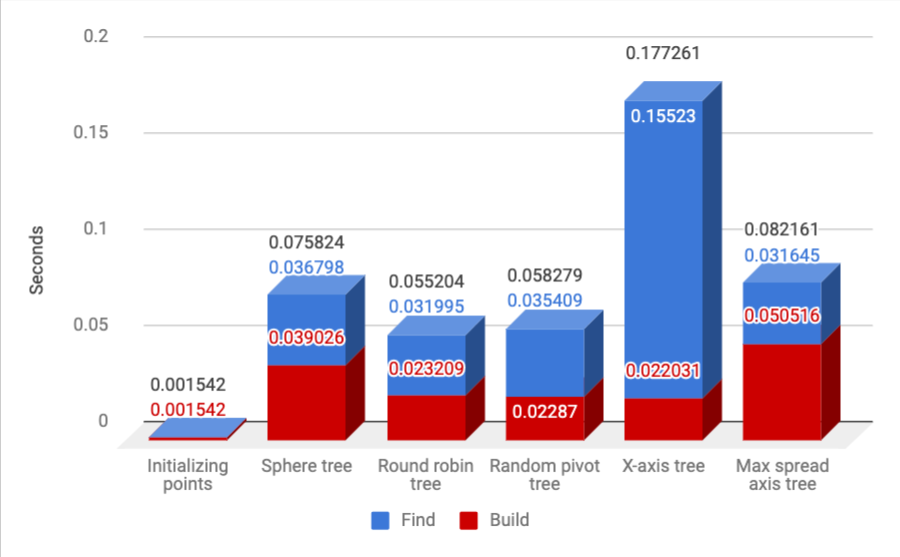

What happens if the points aren’t randomly sampled from the unit cube, like in the experiment above, but are rather organized on the surface of the unit sphere? For this experiment, I kept the slow baseline off, and used 10K points and 10K find-closest queries:

As you can see, the round-robin method still dominates, with the random axis one still very close.

I also tried making the points non-uniformly distributed, like so:

while (std::rand() % 2 == 0) {

(*points)[i] *= 2;

}

So half of the points are around the unit cube (or on the surface of the unit sphere - I tried both configurations), a quarter are doubled, an eighth are quadrupled, etc. As it turns out, almost nothing changes. The above results are almost the same with very slight variations. Round-robin FTW!

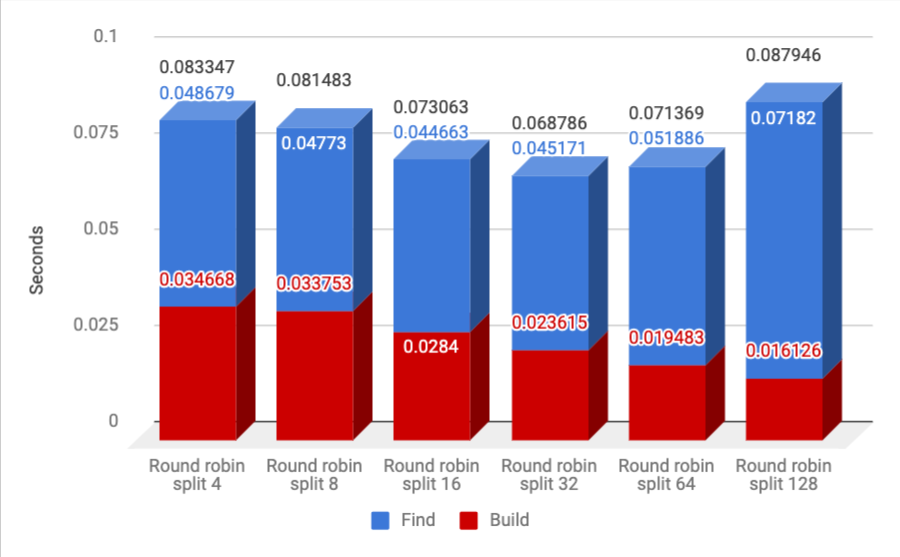

The Effect of the Cutoff

We know there is one more interesting parameter to optimize - the cutoff value, below which we will not keep subdiving the nodes, but rather maintain a flat list. Here we see the results of 10K points in the unit cube in \(R^3\) with 10K queries, using the round-robin axis selection method:

Well, not super surprisingly (that was actually the default I chose before running this experiment :)) it turns out that the best min split size is 32. Obviously the build cost keeps going down as this number increases, but at 32 we are almost minimizing the find cost, while keeping the build cost low.

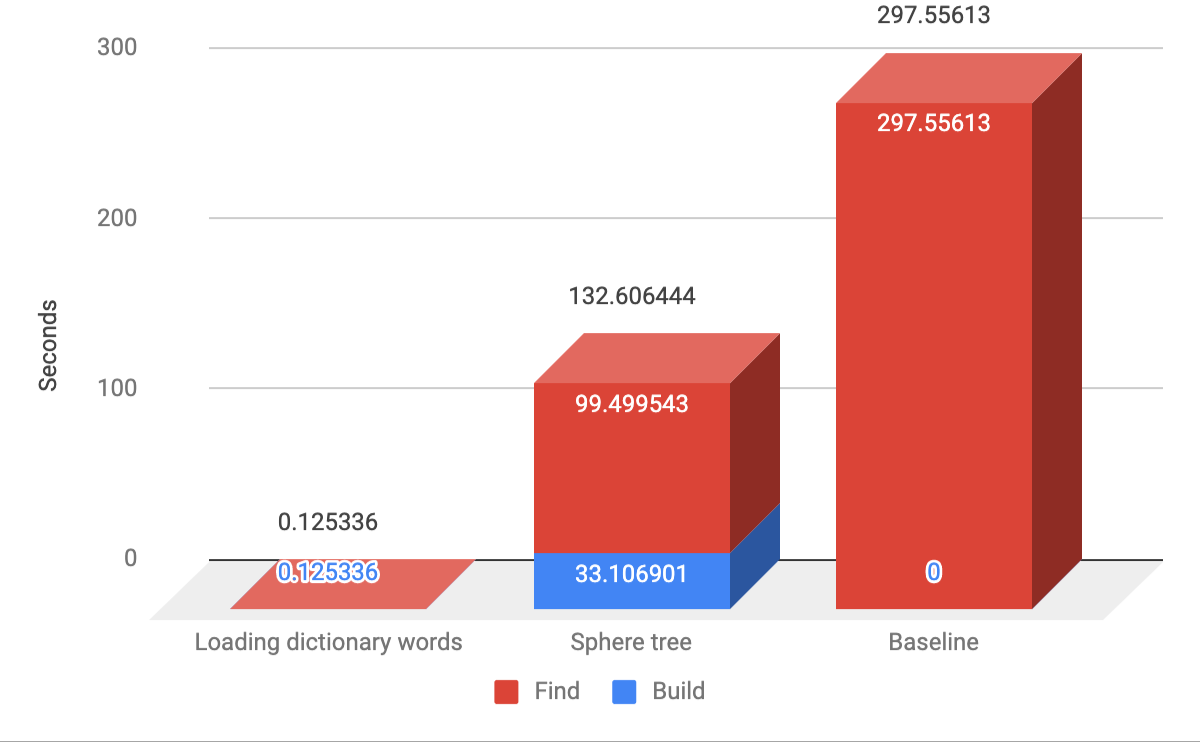

Closest Dictionary String

What about the performance of the data structure for finding the closest strings in the dictionary?

For this experiment I used a dictionary with 194,000 English words (from here). I built the index, and performed 100 closest-word lookups (this was so slow, with such a huge dict, that I only had patience to run 100 iterations). For the target strings, I used random strings of uniform random length between 3 and 10.

Here are the results:

As you can see, this elegant implementation already does much better than the naive approach! There are specialized algorithms for this problem of finding the closest string in a dictionary like SymSpell, LinSpell, or Norvig’s algorithm, but for their gains in time complexity, they pay heavily in memory and code complexity.

Appendix - Calculating Levenshtein Distance

Recall that the Levenshtein distance is a metric on string space (i.e. a distance function between two strings) aiming to measure how similar two strings are. The vanilla Levenshtein distance (that I used for all experiments in this post) is the minimal number of Insert, Remove, and Replace operations required to transform one string into the other (this is the vanilla version in the sense that e.g. all the operations have the same weights, independent on the characters involved, etc.). Here are examples of the three operations:

- Insert: aniv ⟶ Yaniv

- Remove: Yaniiv ⟶ Yaniv

- Replace: Yaniq ⟶ Yaniv

You can easily verify that indeed the Levenshtein distance satisfies all the requirements for a metric.

I originally wrote a trivial recursive (without memoization) Levenshtein distance implementation, like so:

int EditDistanceNaive(const std::string& s1, const std::string& s2,

int len1 = -1, int len2 = -1) {

if (len1 == -1) len1 = s1.length();

if (len2 == -1) len2 = s2.length();

// If s1 is empty, insert all characters of s2.

if (len1 == 0) return len2;

// If s2 is empty, remove all characters of s1.

if (len2 == 0) return len1;

// If the last characters of two strings are same, ignore them.

if (s1[len1 - 1] == s2[len2 - 1])

return EditDistanceNaive(s1, s2, len1 - 1, len2 - 1);

// If the last characters are different, consider all three

// operations on the last character of s1 by recursing and take the minimum.

return 1 + std::min({

EditDistanceNaive(s1, s2, len1, len2 - 1), // Insert.

EditDistanceNaive(s1, s2, len1 - 1, len2), // Remove.

EditDistanceNaive(s1, s2, len1 - 1, len2 - 1) // Replace.

});

}

This was so slow, that I couldn’t run anything but the most trivial of experiments. So I wrote this better implementation, that employees three tricks:

- The naive recursive implementation above recalculates the distance between the same 2 substrings over and over again - this can be easily remedied by using dynamic programming and caching the results of these sub-string comparisons.

- Instead of using an \(n \times m\) matrix (where \(n\) and \(m\) are the lengths of the strings we are comparing), it is enough to use a \(2 \times m\) matrix, as we can scan it top to bottom (see the implementation below), so we use linear memory instead of quadratic memory.

- Finally, since during tree building I am sometimes calculating the distance between the same pair of strings, I wrapped the entire implementation with a version that can cache the full result, so the same strings are never compared more than once in the entire lifetime of the program (for brevity, I omitted this from the implementation below, it’s a simple wrapper on top of EditDistanceNoCache below).

inline const size_t EDIT_DISTANCE_MAX_STRING_LEN = 1024;

class EditDistanceMatrix {

public:

char& operator()(int i1, int i2) { return data[i2 % 2][i1]; }

private:

char data[2][EDIT_DISTANCE_MAX_STRING_LEN];

};

inline int min(int a, int b, int c) { return std::min(a, std::min(b, c)); }

inline int EditDistanceNoCache(const std::string& s1, const std::string& s2) {

CHECK(s1.length() < EDIT_DISTANCE_MAX_STRING_LEN)

<< "The first string must have length <" << EDIT_DISTANCE_MAX_STRING_LEN

<< " (its length is " << s1.length() << ")";

EditDistanceMatrix matrix;

for (int i2 = 0; i2 <= s2.length(); ++i2) {

for (int i1 = 0; i1 <= s1.length(); ++i1) {

if (i2 == 0) {

matrix(i1, i2) = i1;

} else if (i1 == 0) {

matrix(i1, i2) = i2;

} else if (s1[i1 - 1] == s2[i2 - 1]) {

matrix(i1, i2) = matrix(i1 - 1, i2 - 1);

} else {

matrix(i1, i2) = 1 + min(matrix(i1 - 1, i2), matrix(i1, i2 - 1),

matrix(i1 - 1, i2 - 1));

}

}

}

return matrix(s1.length(), s2.length());

}

All the above experiments use this implementation.

Implementation

Finally, here is my implementation of the spatial partition data structure in C++:

/*

Generic spatial-partition binary tree.

*/

#pragma once

#include <cmath>

#include <memory>

#include <numeric>

#include <optional>

#include <vector>

#include "logging.h"

#include "str_util.h"

#include "vec3.h"

namespace spatial_partition {

template <class T, class Compare>

size_t MedianIndexAndPartialSort(std::vector<T>& v,

const Compare& comp = std::less<T>()) {

size_t median_index = v.size() / 2;

std::nth_element(v.begin(), v.begin() + median_index, v.end(), comp);

return median_index;

}

// Non-negative distance between two points to be compared.

template <class ValueType>

using DistanceFunc = float (*)(const ValueType&, const ValueType&);

template <class ValueType>

using GetRadiusFunc = float (*)(const ValueType&);

template <class ValueType>

float ZeroRadius(const ValueType& t) {

return 0;

}

struct RelationToHypersurface {

RelationToHypersurface(float signed_distance, float radius) {

if (radius == 0) this->signed_distance = signed_distance;

float distance_from_radius = std::abs(signed_distance) - radius;

if (distance_from_radius > 0) {

this->signed_distance =

std::copysign(distance_from_radius, signed_distance);

} else { // item intersects the hyperplane.

this->signed_distance = 0;

}

}

bool intersects() { return signed_distance == 0; }

size_t side() { return signed_distance < 0 ? 0 : 1; }

size_t otherSide() { return 1 - side(); }

float distance() const { return std::abs(signed_distance); }

private:

float signed_distance;

};

template <class ValueType>

using RelationToHypersurfaceFunc = RelationToHypersurface (*)(const ValueType&);

// A hyperplane in R3 perpendicular to one of the Axes.

struct AxisAlignedHyperplane {

vec3::Axis perpendicular_axis = vec3::X;

float intersection_coord;

std::string str() const {

return std::string("AxisAlignedHyperplane(") +

to_string(perpendicular_axis) + '@' +

std::to_string(intersection_coord) + ')';

}

};

template <class ValueType>

struct SphereHypersurface {

ValueType center;

float radius;

std::string str() const {

return std::string("SphereHypersurface(center: ") + center +

", radius: " + std::to_string(radius) + ")";

}

};

template <class ValueType, class Hypersurface>

RelationToHypersurface relation(const Hypersurface& hypersurface,

const ValueType& item) {

float item_value_in_axis =

static_cast<vec3>(item)[hypersurface.perpendicular_axis];

float distance_from_pivot_in_axis =

item_value_in_axis - hypersurface.intersection_coord;

return RelationToHypersurface(distance_from_pivot_in_axis, 0);

}

template <>

RelationToHypersurface relation<vec3, AxisAlignedHyperplane>(

const AxisAlignedHyperplane& hyperplane, const vec3& item) {

float item_value_in_axis = item[hyperplane.perpendicular_axis];

float distance_from_pivot_in_axis =

item_value_in_axis - hyperplane.intersection_coord;

return RelationToHypersurface(distance_from_pivot_in_axis, 0);

}

template <class ValueType, DistanceFunc<ValueType> Distance>

RelationToHypersurface relationToSphere(

const SphereHypersurface<ValueType>& sphere, const ValueType& item) {

float distance_from_center = Distance(item, sphere.center);

float distance_from_sphere_border = distance_from_center - sphere.radius;

return RelationToHypersurface(distance_from_sphere_border, 0);

}

template <>

RelationToHypersurface relation<vec3, SphereHypersurface<vec3>>(

const SphereHypersurface<vec3>& sphere, const vec3& item) {

return relationToSphere<vec3, dist>(sphere, item);

}

float EditDistanceFloat(const std::string& s1, const std::string& s2) {

return EditDistance(s1, s2);

}

template <>

RelationToHypersurface relation<std::string, SphereHypersurface<std::string>>(

const SphereHypersurface<std::string>& sphere, const std::string& item) {

return relationToSphere<std::string, EditDistanceFloat>(sphere, item);

}

template <class ValueType = vec3>

struct AxisComparator {

AxisComparator(vec3::Axis axis) : axis(axis) {}

vec3::Axis axis;

bool operator()(const ValueType& a, const ValueType& b) {

return static_cast<vec3>(a)[axis] < static_cast<vec3>(b)[axis];

}

};

template <class ValueType = vec3>

struct MaxSpreadAxisSelector {

vec3::Axis selectAxis(const std::vector<ValueType>& items) const {

std::vector<float> xs, ys, zs;

for (const ValueType& item : items) {

const vec3 pos = static_cast<vec3>(item);

xs.push_back(pos.x);

ys.push_back(pos.y);

zs.push_back(pos.z);

}

float x_spread = spread(xs);

float y_spread = spread(ys);

float z_spread = spread(zs);

if (x_spread > y_spread && x_spread > z_spread) {

return vec3::X;

} else if (y_spread > z_spread) {

return vec3::Y;

} else {

return vec3::Z;

}

}

MaxSpreadAxisSelector child() const { return *this; }

private:

static float spread(const std::vector<float>& v) {

const auto [min, max] = std::minmax_element(begin(v), end(v));

return *max - *min;

}

};

template <class ValueType = vec3>

struct XAxisSelector {

vec3::Axis selectAxis(const std::vector<ValueType>& items) const {

return vec3::X;

}

XAxisSelector child() const { return *this; }

};

template <class ValueType = vec3>

struct RandomAxisSelector {

vec3::Axis selectAxis(const std::vector<ValueType>& items) const {

return vec3::Axis(std::rand() % 3);

}

RandomAxisSelector child() const { return *this; }

};

template <class ValueType = vec3>

struct RoundRobinAxisSelector {

vec3::Axis axis = vec3::X;

vec3::Axis selectAxis(const std::vector<ValueType>& items) const {

return axis;

}

RoundRobinAxisSelector child() const {

return RoundRobinAxisSelector{vec3::Axis((axis + 1) % 3)};

}

};

template <class ValueType = vec3, class AxisSelector = RoundRobinAxisSelector<>>

struct AxisAlignedHyperplaneSelector {

AxisSelector axis_selector;

typedef AxisAlignedHyperplane Hypersurface;

AxisAlignedHyperplane selectHypersurface(

std::vector<ValueType>& items) const {

vec3::Axis axis = axis_selector.selectAxis(items);

AxisComparator<ValueType> cmp(axis);

int median_index = MedianIndexAndPartialSort(items, cmp);

ValueType median_item = items[median_index];

float value = static_cast<vec3>(median_item)[axis];

return AxisAlignedHyperplane{axis, value};

}

AxisAlignedHyperplaneSelector child() const {

return AxisAlignedHyperplaneSelector{axis_selector.child()};

}

};

template <class ValueType = vec3, class AxisSelector = RoundRobinAxisSelector<>>

struct RandomAxisAlignedHyperplaneSelector {

AxisSelector axis_selector;

using Hypersurface = AxisAlignedHyperplane;

AxisAlignedHyperplane selectHypersurface(

std::vector<ValueType>& items) const {

int index = std::rand() % items.size();

const ValueType& item = items[index];

vec3::Axis axis = axis_selector.selectAxis(items);

float value = ToVec3(item)[axis];

return AxisAlignedHyperplane{axis, value};

}

RandomAxisAlignedHyperplaneSelector child() const {

return RandomAxisAlignedHyperplaneSelector{axis_selector.child()};

}

};

template <class ValueType = vec3, DistanceFunc<ValueType> Distance = dist>

struct HalfMaxDistSphereSelector {

using Hypersurface = SphereHypersurface<ValueType>;

Hypersurface selectHypersurface(std::vector<ValueType>& items) const {

int index = std::rand() % items.size();

const ValueType& pivot_item = items[index];

// std::cerr << "HalfMaxDistSphereSelector selected random pivot: "

// << pivot_item << std::endl;

float max_dist = 0;

for (const ValueType& item : items) {

float cur_dist = Distance(item, pivot_item);

max_dist = std::max(max_dist, cur_dist);

// std::cerr << pivot_item << ' ' << item << ' ' << cur_dist << ' '

// << max_dist << std::endl;

}

float radius = max_dist / 2;

return SphereHypersurface<ValueType>{pivot_item, radius};

}

HalfMaxDistSphereSelector child() const {

return HalfMaxDistSphereSelector{};

}

};

template <class ValueType = vec3, DistanceFunc<ValueType> Distance = dist>

struct DistanceFromFixedElementComparator {

DistanceFromFixedElementComparator(const ValueType& pivot) : pivot(pivot) {}

ValueType pivot;

bool operator()(const ValueType& a, const ValueType& b) {

return Distance(pivot, a) < Distance(pivot, b);

}

};

template <class ValueType = vec3, DistanceFunc<ValueType> Distance = dist>

struct MedianDistSphereSelector {

using Hypersurface = SphereHypersurface<ValueType>;

Hypersurface selectHypersurface(std::vector<ValueType>& items) const {

int index = std::rand() % items.size();

const ValueType& pivot_item = items[index];

int median_index = MedianIndexAndPartialSort(

items,

DistanceFromFixedElementComparator<ValueType, Distance>(pivot_item));

float median_dist = Distance(pivot_item, items[median_index]);

float radius = median_dist;

return SphereHypersurface<ValueType>{pivot_item, radius};

}

MedianDistSphereSelector child() const { return MedianDistSphereSelector{}; }

};

template <int Size>

struct SplitSize {

// TODO: think about this.

static_assert(Size >= 3, "Size must be at least 3");

const static int size = Size;

};

template <class ValueType = vec3, class Hypersurface = AxisAlignedHyperplane,

class HypersurfaceSelector = AxisAlignedHyperplaneSelector<

ValueType, RoundRobinAxisSelector<ValueType>>,

DistanceFunc<ValueType> Distance = dist,

class MaxSplit = SplitSize<32>>

class Tree {

public:

void fromVector(const std::vector<ValueType>& vec) {

for (const auto& item : vec) {

add(item);

}

compile();

}

void add(const ValueType& item) {

CHECK(!_compiled) << "Trying to add elements after tree compilation";

items.push_back(item);

}

Tree* child(int index) {

CHECK(index < 2) << "Invalid index for child " << index;

if (!_children[index]) {

_children[index] = std::make_unique<Tree>();

}

return _children[index].get();

}

void compile(const HypersurfaceSelector& hypersurface_selector =

HypersurfaceSelector()) {

_compiled = true;

if (items.size() <= MaxSplit::size) {

return;

}

hypersurface = hypersurface_selector.selectHypersurface(items);

splitItemsToChildren();

if (_children[0] != 0) {

_children[0]->compile(hypersurface_selector.child());

}

if (_children[1] != 0) {

_children[1]->compile(hypersurface_selector.child());

}

}

void splitItemsToChildren() {

std::vector<ValueType> all_items;

std::swap(items, all_items);

for (const ValueType& item : all_items) {

RelationToHypersurface item_to_hypersurface =

relation(*hypersurface, item);

if (item_to_hypersurface.intersects()) {

items.push_back(item);

} else {

child(item_to_hypersurface.side())->add(item);

}

}

}

struct ItemWithDistance {

ValueType item;

float distance = std::numeric_limits<float>::infinity();

std::string str() const {

return std::string("ItemWithDistance(") + item +

", dist: " + std::to_string(distance) + ")";

}

static const ItemWithDistance& min(const ItemWithDistance& i1,

const ItemWithDistance& i2) {

if (i1.distance < i2.distance) return i1;

return i2;

}

};

bool isLeaf() const { return !hypersurface.has_value(); }

ItemWithDistance findClosest(const ValueType& target) const {

CHECK(_compiled) << "Trying to use Tree without compiling it first.";

ItemWithDistance res;

for (const ValueType& item : items) {

float distance = std::max<float>(0, Distance(item, target));

res = ItemWithDistance::min(res, ItemWithDistance{item, distance});

if (res.distance == 0) return res;

}

if (!isLeaf()) {

RelationToHypersurface target_to_hypersurface =

relation(*hypersurface, target);

Tree* child_with_target = _children[target_to_hypersurface.side()].get();

if (child_with_target) {

res =

ItemWithDistance::min(res, child_with_target->findClosest(target));

if (res.distance == 0) return res;

}

Tree* child_without_target =

_children[target_to_hypersurface.otherSide()].get();

if (child_without_target &&

target_to_hypersurface.distance() < res.distance) {

res = ItemWithDistance::min(res,

child_without_target->findClosest(target));

}

}

return res;

}

std::string str(int depth = 0) const {

std::string res = std::string(depth, ' ');

if (hypersurface.has_value()) {

res += hypersurface->str() + "\n";

}

if (_children[0] != 0) {

res += std::string(depth, ' ') + "left:\n" + _children[0]->str(depth + 1);

}

if (_children[1] != 0) {

res +=

std::string(depth, ' ') + "right:\n" + _children[1]->str(depth + 1);

}

if (items.size() > 0) {

res += std::to_string(items.size()) +

" items:" + JoinAsStrings<ValueType>(items) + "\n";

}

return res;

}

private:

std::vector<ValueType> items;

std::optional<Hypersurface> hypersurface;

std::unique_ptr<Tree> _children[2];

bool _compiled = false;

};

template <class ValueType, DistanceFunc<ValueType> Distance,

class MaxSplit = SplitSize<32>>

using KDTree = Tree<

ValueType, AxisAlignedHyperplane,

AxisAlignedHyperplaneSelector<ValueType, RoundRobinAxisSelector<ValueType>>,

Distance, MaxSplit>;

template <class AxisSelector, class MaxSplit = SplitSize<32>>

using CustomVec3KDTree = Tree<vec3, AxisAlignedHyperplane,

AxisAlignedHyperplaneSelector<vec3, AxisSelector>,

dist, SplitSize<32>>;

template <class ValueType, DistanceFunc<ValueType> Distance,

class MaxSplit = SplitSize<32>>

using VPTree =

Tree<ValueType, SphereHypersurface<ValueType>,

MedianDistSphereSelector<ValueType, Distance>, Distance, MaxSplit>;

using Vec3KDTree = KDTree<vec3, dist>;

using Vec3VPTree = VPTree<vec3, dist>;

using StringVPTree = VPTree<std::string, EditDistanceFloat, SplitSize<1024>>;

} // namespace spatial_partition

Hope you enjoyed reading this as much as I enjoyed writing it!

PS - until I write the full post about it, here is a quick teaser from my General Relativity Renderer, rendering a million stars with a black hole in the middle:

More on that soon!