This topic is about defining a weird game and exploring its properties. When I first encountered it I could not help but wonder, why is it interesting?

Well, this game (as you shall soon find out for yourself) has barely any practical implications. But it is an interesting subject none the less. There are 2 main reasons for that:

- This game was analysed (with limited success) by many important mathematicians, since the times of the Greeks.

- Using the right tools, the complete answer to the questions relating this matter is achievable and it turns out to be beautiful.

Now lets dive in. We will begin with a simplified game I call “Constructions with a Straight-Edge Only”. BTW, a straight-edge means a ruler without markings (so the only thing you can do with a straight-edge is connect two points with an infinite line).

These are the rules of our simplified game: The board is the 2 dimensional euclidean plane. You start with an initial set of points and during the game you make it grow. Lets call this set of points P. On each turn you can connect two points in your set P by an infinite straight line. If two of these lines intersect at one point that is not already in P, the new point is added to P.

A point of the euclidean plane is called constructable (from the original points) if it can be added to P.

Some Simple Examples:

- If the initial set of points consists of only a single point then this single point is also the only constructable point (as no lines can be drawn). The same applies for an initial set containing 2 points (as only one line can be drawn, and so there are no line intersections!).

- If the initial set contains 3 points then 3 lines can be drawn (as shown here). But no new point is created.

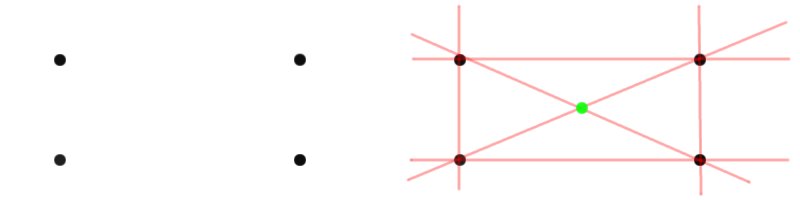

If the initial set is a rectangle, one new point can be created.

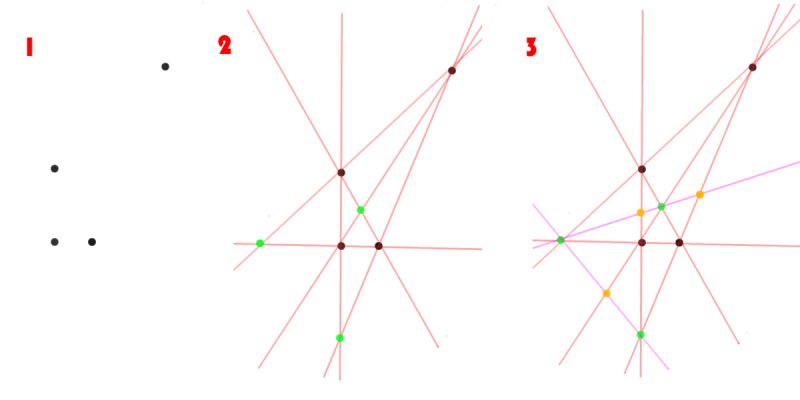

A more complex example is depicted below. Well, as you can see, many new points can be created. I added to the illustration only the first few, but hopefully you get the point (pun not intended).

Question: What initial sets of points (if any) lead to an infinite set of constructable points?

Note that we have not specified that the initial set should be finite. For example, we can start out with all the points on the x-axis. It is clear that the set of points constructable from this set is equal to the x-axis (i.e. no new point can be constructed).

The above example suggests another interesting question – what initial sets of points are unexpandable? I.e. no new points can be constructed from them. The sets containing fewer than 4 points are obviously unexpandable, as are the sets contained in a line and the set consisting of the entire euclidean-plane. But are there others?

Now lets assume our initial set contains only points with rational coordinates (lets call them rational points). What can be said about the set P of constructable points?

A nice observation is that P contains only rational points. To see this, observe that each point \((x, y)\) of the line passing through points \((x1, y1)\) and \((x2, y2)\) satisfies the equation:

\[y = (x – x1) \times \frac{y2 – y1}{x2 – x1} + y1\]Opening all the parenthesis, and noting that the set of rational numbers constitutes a field, the line equation becomes:

\[y = m \times x + b\]Where \(m\) and \(b\) are rational numbers.

Note that if the line is vertical it does not satisfy the equation but since it is clear how to handle this special-case I will not elaborate.

It suffices therefore to show that the point of intersection of two lines of the form:

\[y = m \times x + b\]and

\[y = m' \times x + b'\]is rational (i.e. it has rational coordinates). Since the point of intersection \((x_0, y_0)\) satisfies both line equations, we get:

\[m \times x_0 + b = m' \times x_0 + b'\]or

\[x_0 = \frac{b' – b}{m – m'}\]and so \(x_0\) is rational (again, I ignore the special case \(m = m'\) in which the lines are parallel).

And then \(y_0 = m \times x_0 + b\) is also rational. So indeed the intersection of two lines passing through two rational points is a rational point. \(\blacksquare\)

This concludes the first part of this topic.