In this post (and its sequel) I will describe Hilbert’s 3rd problem and show how it is solved. I based the posts mainly on a lecture by Prof. David Gilat.

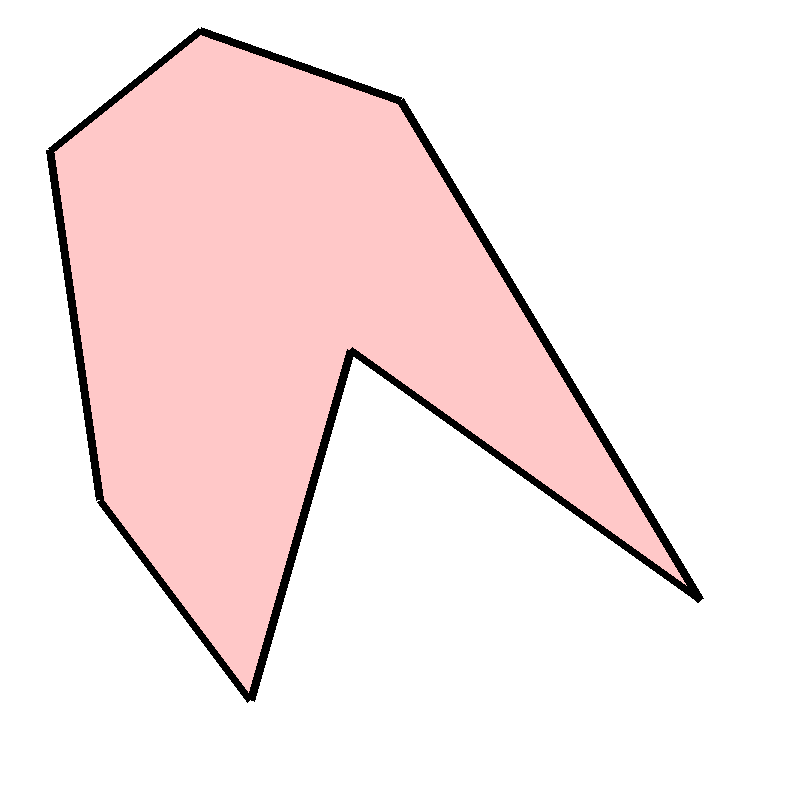

Let’s begin by considering a polygon in the Euclidean plane. Here is an example of such a polygon:

We want to devise a method for somehow “measuring” the area of this and similar polygons.

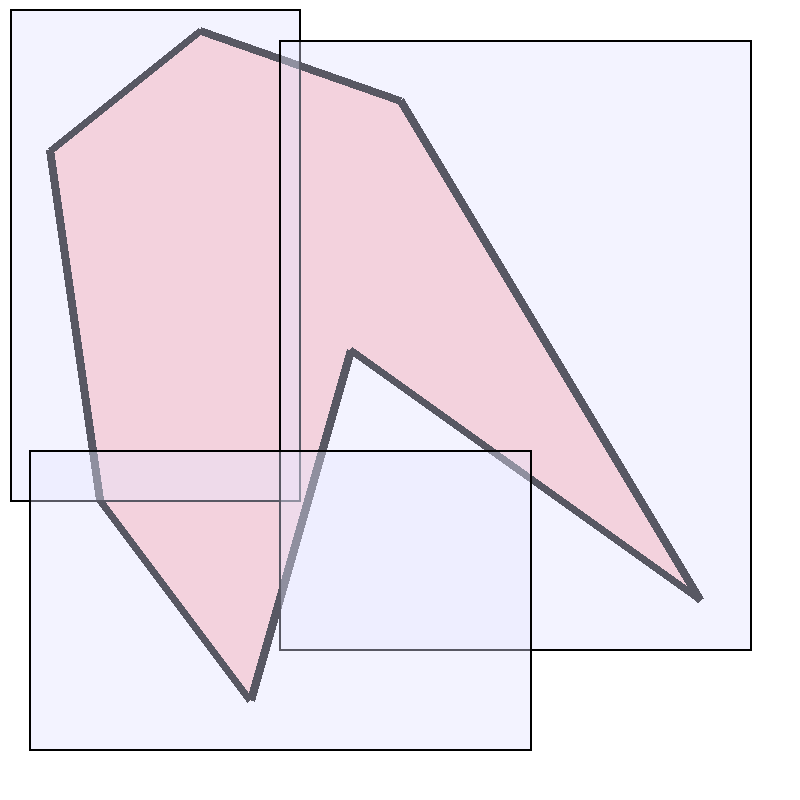

In order to do this, we begin by defining the area of a rectangle that is parallel to the coordinate axes as the product of its horizontal side by its vertical side.

We now define the area of a polygon to be the infimum of the sum of all the areas of sets of rectangles that constitute a covering of the polygon. An example of such a covering (using 3 rectangles) is depicted here:

This is the Lebesgue measure of the polygon. This area happens to have some very desirable properties:

- It is invariant to translations (i.e. a polygon’s area will remain the same if it is moved to a different location in the plane).

- It is invariant to rotations (i.e. a polygon’s area will remain the same if it is rotated).

- It is invariant to reflections (i.e. a polygon’s area will remain the same if it is reflected over any straight line).

- It has the finite-additivity property (explained below).

I will not prove these properties here as it is very easy and somewhat tedious to do so.

Let’s focus on the last property, namely finite-additivity. Finite-additivity means that if we take two polygons that are disjoint (actually, that have disjoint interior) and regard their union as one new polygon, then the area of the new polygon will be equal to the sum of the areas of the two original polygons.

Let’s call two polygons, P and Q, congruent in parts, if we can divide P to polygons \(p_1, ..., p_n\) and Q to polygons \(q_1, ..., q_n\) such that \(p_i\) can be obtained from \(q_i\) by a finite number of translations, rotations and reflections.

The properties of area listed above, give the following important (though a little obvious) conclusion:

Theorem 1: Two polygons P and Q that are congruent in parts have the same area.

It suffices, by finite-additivity, to show that the areas of the polygons \(p_i\) and \(q_i\) are the same for all i. But by the invariance of the area under rotations, translations and reflections, this is obvious.

Now an interesting question arises: Given two polygons P and Q that have an equal area, are they congruent in parts?

The question can be given an affirmative answer. Let’s give an outline of the proof:

- Every polygon can be divided to finitely many triangles. This is obvious in the case of a convex polygon. In the case of a concave polygon, select any diagonal that lies completely inside the polygon. This diagonal divides the polygon into two polygons each with fewer sides than the original. By induction we can divide the polygon into finitely many triangles. It still remains to be shown that we can always find a diagonal that lies completely inside our polygon, but that is not hard (I will leave this as an exercise to the reader :-) ).

- Every triangle is congruent in parts to a rectangle (see illustrations below).

- Every rectangle is congruent in parts to a square.

- Two squares are congruent in parts to a square whose area is the sum of their areas.

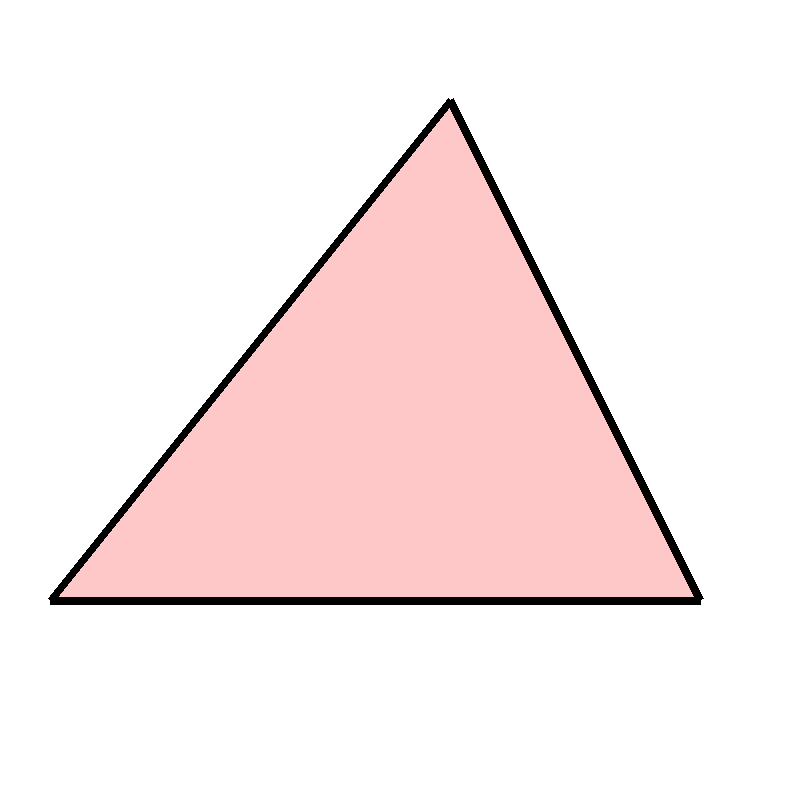

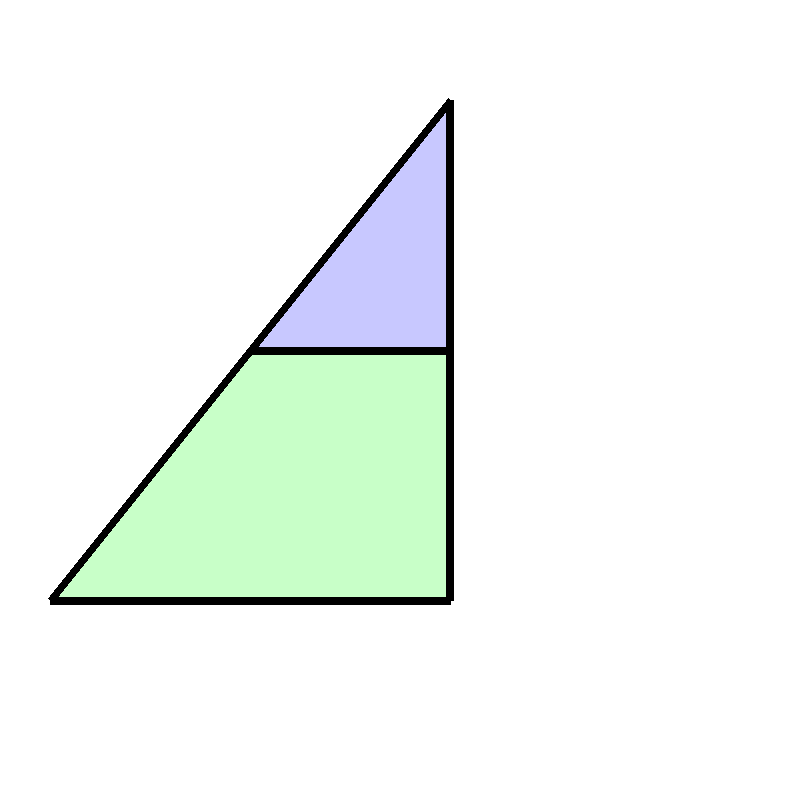

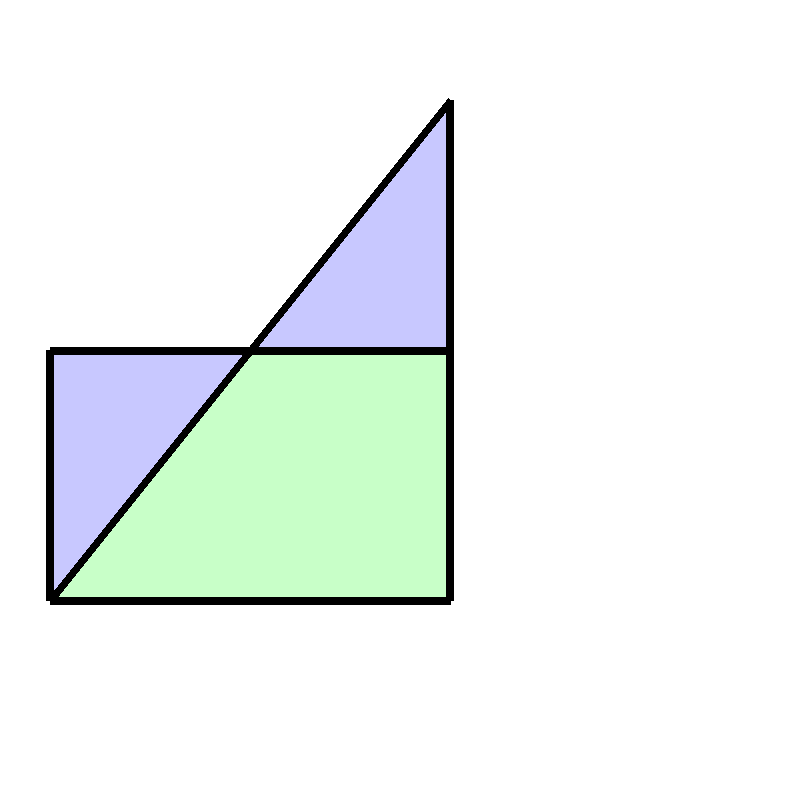

Let’s show that a triangle is congruent in parts to a rectangle. Start with a triangle:

Any triangle can be split to 2 right-angle triangles:

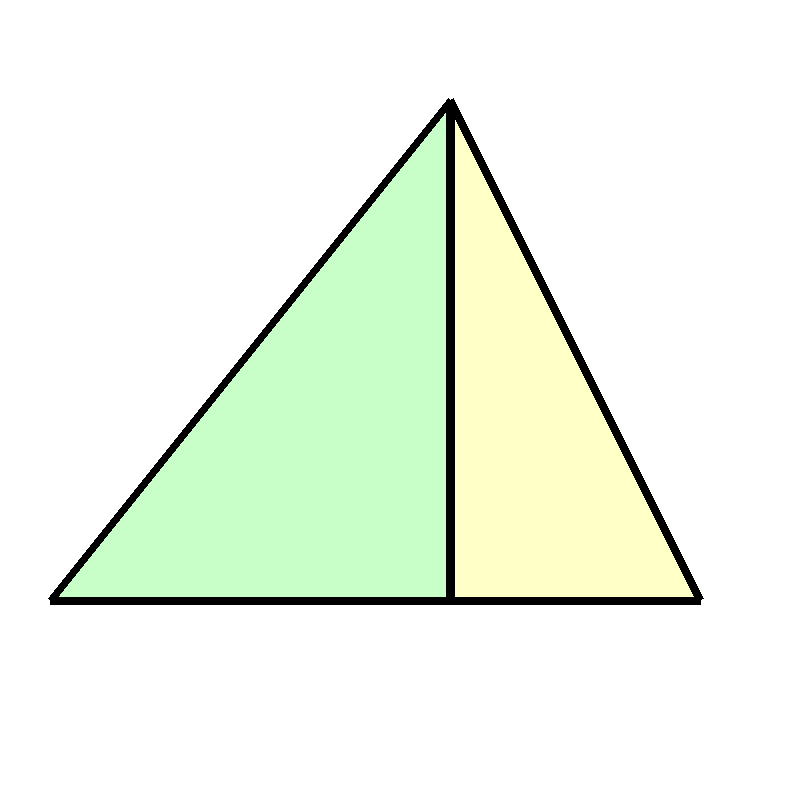

So it’s enough to consider right triangles. We cut the right triangle, parallel to the base, mid height:

And we finish by noticing that these blue parts are the same:

We have shown that every polygon is congruent in parts to a square of the same area. We thus have the inverse of Theorem 1, namely,

Theorem 2: Two polygons that have the same area are congruent in parts.

On to three dimensions. We define a polyhedron’s volume (a polyhedron is the three dimensional analogue of a polygon), it’s Lebesgue measure, in a completely analogous way to the two dimensional Lebesgue measure. Given a box whose facets are parallel to the coordinate plane we define its volume to be the product of three of its perpendicular sides. Given any polyhedron we now define its volume as the infimum of the sum of the volumes of all the boxes in a covering of the polyhedron, where the infimum is taken over all the countable coverings of the polyhedron by boxes with facets parallel to the coordinate planes.

We say that two polyhedrons are congruent in parts if we can divide them into polyhedrons \(p_1, ..., p_n\) and \(q_1, ..., q_n\) such that the \(p_i\)’s have disjoint interiors (and similarly for the \(q_i\)’s) and such that \(q_i\) can be obtained from \(p_i\) by translations, rotations and reflections (around planes).

The three dimensional Lebesgue measure has the same properties as the two dimensional Lebesgue measure mentioned above. Thus Theorem 1 can be generalized to:

Theorem 3: Two polyhedrons that are congruent in parts have the same volume.

It was conjectured by Gauss that Theorem 3’s inverse (the generalization of Theorem 2 to three dimensions) does not hold. This question later became known as Hilbert’s Third Problem (see Hilbert’s Problems).

Let’s state it again, for clarity:

Hilbert’s Third Problem: Are two polyhedrons that have the same volume necessarily congruent in parts?

One might try to answer the question affirmatively by employing a method similar to the one we used for Theorem 2. I.e. find a “generic” 3D polyhedron (the 3D analogue of the 2D triangle) and divide the polyhedrons to finitely many such “generic” polyhedrons. The problem is that, contrary to the 2D triangle, the existence of such a “generic” polyhedron is not obvious.

The problem was indeed given a negative answer by Hilbert’s student Max Dehn. Dehn managed to construct a function D of polyhedrons that remained invariant under congruence in parts (i.e. two polyhedrons that are congruent in parts produce the same value of D). He managed to show that the values of D on the regular tetrahedron and on the cube are different even if they have the same volume.

Dehn’s invariant, D, is defined as follows:

\[D(P) = \sum_{m \in edges(P)} l(m)f(q(m))\]Where the \(\sum\) is taken over all edges m of the polyhedron, l(m) denotes the length of the edge, q(m) denotes the angle between the two planes formed by the facets m connects, and finally \(f:\mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{Q}\) is a linear transformation (from the real line into the field of rational numbers, where \(\mathbb{R}\) is regraded as an infinite dimensional vector space over \(\mathbb{Q}\)) with the following properties:

- \[f(1) = 0\]

- \[f(qx) = qf(x), q \in \mathbb{Q}, x \in \mathbb{R}\]

- \[f(x + y) = f(x) + f(y)\]

- \[f(p_i) = 0\]

- \(f(x) \neq 0\), if x is not linearly dependent on \(p_i\) and 1 (again, regarding \(\mathbb{R}\) as a vector space over \(\mathbb{Q}\)).

Cautious readers might notice that the existence of such a function depends on the axiom of choice (as it relies on the possibility of constructing a base for R, when regarded as a vector space over Q). Such a construction is not really necessary, i.e. the theorem does not depend upon the axiom of choice. I leave the matter of arranging a finite dimensional vector space over Q that is sufficient for the proof as an exercise to the reader.

In the next installment of the series I will prove that Dehn’s invariant is indeed an invariant (under congruence in parts), and calculate its value for the cube and for the tetrahedron, thus finishing the proof.

To Be Continued…